You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping …Versus One Hit But Impressive

…Versus One Hit But Impressive

One Sunday evening many years ago I was watching the weekend’s edition of the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s Countdown, the country’s then premier popular music showcase. The ABC production had held the mantle since coming to the airwaves in the mid-seventies. The programme immediately gripped the (youthful) public’s imagination and captured a phenomenal viewing audience. Finally, those who were at an age when popular music meant the world could look at and listen to both Australian and overseas artists in an hour-long format. Frequently, Countdown’s invitees appeared in the flesh, miming, performing their tunes live to air or a combination of the two. Music videos, then becoming a key promotional tool, of singers and bands comprised much of the rest of the content.

My siblings and I regarded the hour as tantamount to requisite viewing though in all truth it never assumed hallowed status in the eyes of any of us. The curious mixture of weightless fare – wallpaper music, to borrow John Lennon’s term – and evocative songs that stayed with one after the listening experience ended bemused and fascinated in equal measure. The reason I still tuned in from time to time was on the off chance a gem might show its face.

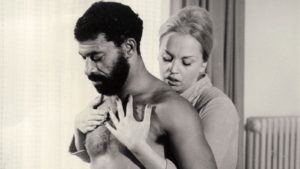

That Sunday evening a slightly built young man took the stage and completely galvanised with his three to four-minute rendition. How the ebullient Countdown groupies on the floor responded to him I no longer recall. But I was not the only one deeply impressed. The host that night, Skyhooks’ Bongo Starkey, waxed lyrical about the performer’s talent in a few brief words uttered on camera when the song ended.

As a direct result of the exposure, many of the groups and singers featured on Countdown reached the top of the Australian charts. This exposure and corresponding success generally continued if their later musical output kept winning the favour of the programme’s godfather figure Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum, transforming them into a selling point more substantial and lasting than your run-of-the-mill one-hit wonder.

At the same time, the songs with which not a few rode to popularity were not unlike those that would in other circumstances bring an artist or group to the heights for the briefest of interludes only. They wore the veneer of pop with a capital p; theirs was the sort of music one might paper one’s walls with and many in the viewing audience must have sighed with relief that one solitary hit was the extent of it – and them!

But I thought it unfortunate that the mystery singer similarly sank without a trace. And without gaining commercial success with the song he performed that night. Molly’s stamp of approval was by no means guaranteed to work the same magic for all who appeared of a Sunday night, especially when it came to performers who belonged outside the common run, as ‘Mr X’ assuredly did. Something about him smacked of a genuine talent, perhaps sealing his fate as a ‘one-hit man without a hit’.

*

To shift the discussion a few degrees, the epithets ‘great artist’ or ‘great art’ are ofttimes bandied about in the arts. Alas, they are overused, an overuse that reflects ignorance of the fact that greatness as an artist, or indeed in any field of human endeavour, rarely occurs overnight. Lofty status is unlikely to arise without steadfast dedication and exacting work over an extended period of time. Needless to say, as with the valuation of the quality of beauty, there is subjectivity involved in making the judgement. The output of writers, musicians, filmmakers, painters and other artists affect people differently and shall always do so. But greatness, like truth, is not theoretical or speculative. Nor is it dependent on a critic’s intellectual insight. It simply is.

Hermann Hesse in his masterful novel Steppenwolf (1927) doffs his hat to Mozart and Goethe. Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels often contain a nod to Franz Kafka. Few classical music and literature aficionados would dispute the ‘selections’ of either Hesse or Ishiguro. By the same token, many admirers of the work of these ‘apprentices’ would consider them latter-day greats too. Hesse wrote many novels over the course of a long life. The distance he travelled between Peter Camenzind (1904) and The Glass Bead Game (1943) was considerable. His growth as an artist is there to behold. He never ‘rehashed’ his novels. In each he varied and developed his pet themes and worldview, meeting what might be considered one prerequisite for greatness. The same holds true with the ongoing career of Ishiguro. Nothing is more tiresome than an artist who, having found his niche, then repeats himself … and repeats himself! This is indicative not of talent but a dearth of ideas.

In his autobiography My Last Sigh (1983) the filmmaker Luis Buñuel makes the point that he never argued about money. Nor did any amount of money induce him to make a film that he did not wish to make, he said. The inference that might be drawn from this is that he received offers in Europe and/or the Americas, but never allowed money considerations to trump his artistic integrity. To put it another way, he refused to sell out. Such an uncompromising stance when it comes to their vision of the world would be a characteristic of many of the ‘great’. Their works are like no other. They are not made with an audience in mind or for an audience. Paradoxically, if they are made and/or gain an airing they can garner widespread appeal.

The careers of the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima were relatively short in terms of years. Fassbinder self-destructed at the age of thirty-seven after a flurry of productivity almost unprecedented in a creative artist. In the space of less than a decade and a half, he wrote and directed more than forty features, films for television, television series and theatre productions. Mishima, the self-confessed ‘boy who wrote poetry’, was also highly prolific until he committed seppuku in his mid-forties.

Neither could claim longevity in their respective fields, natural-born for them as the two were. They burned brightly nonetheless. It is tempting to imagine the artists they might have evolved into had they lived to grand old ages. Mature visions may result in the most extraordinary works of art. The Glass Bead Game, Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964) and Ordet (1955), Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), the film trilogies Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman made in the 1960s, several of Carlos Saura’s 1970s and 80s productions … all are the works of skilled practitioners at the peak of their powers.

*

In the early 1980s, a recurring, highly popular double feature on the schedule at an old repertory cinema in inner Melbourne was an idiosyncratic French pairing Bof (1971), also known as Who Cares: Anatomy of a Delivery Boy, and Themroc (1973). Director Claude Faraldo made other films subsequently but none possessed the same quirky vision and style. Jaime Chávarri, the Spanish auteur, demonstrated moving cinema artistry in To An Unknown God (1977) and Dedicatoria (A dedication) (1980). Like Faraldo, he made other films. But his development as an artist stalled for many years when he turned to more commercial projects. Thankfully, his film Camarón (2005), a biopic of a talented but troubled Flamenco singer, signalled a long-awaited return to his best.

The pressure for a ‘sequel’, or to as soon as possible follow up on something highly successful, may ruin artists who do not have a sequel in them. Bowing to the pressure can result in the fabrication of substandard product. The irony is that were they left alone other good work might follow in time. The necessary lapse should not be begrudged because of market forces. A vision worthy of the name needs time to develop.

‘Sequel mania’ applies especially to filmmakers. Good sequels are made, but there are many more bad sequels than good. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part Two (1974) is at least the equal of The Godfather Part One (1972). But Part Three (1990) was one too many, almost a parody of the earlier films. Both The Omen (1976) and The Exorcist (1973) franchises sputtered out when producers sought to cash in on the innovation and success of the lead-off films. With the benefit of hindsight, both ought to have been left to stand alone, and stand the test of time, on whatever originality they contained.

Writers and other artists can be pushed to satisfy the rabid thirst for sequels too. Genre fiction writers often intentionally set themselves up to construct swathes of novels around a particular character who has ‘clicked’ with the reading public. Other writers will even take it upon themselves to pen further adventures of those characters long after their original creator has died. Two examples would be the late Robert Ludlum and his fictional maverick spy Jason Bourne and the late Stieg Larsson and his spunky heroine Lisbeth Salander. Literary fiction writers, on the other hand, will find any such insistence harder to deal with. Robert Pirsig burst onto the scene as if out of nowhere with Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974). It would be many years before its ‘sequel’ Lila (1991) graced the bookshelves. If there existed pressure on the author to waste no time in trying to emulate the runaway success of Zen, he can be congratulated on resisting it as long as he did.

*

There is much to be said for longevity, as Dr Martin Luther King reminded us. It may be more elusive in the pop music realm, however, where any genuine aspirant has to line up in a field renowned for disposability and blandness. Pete Townshend, of The Who, maintained that popular music deserved to be taken as seriously as the other arts. To his credit, much of his output, the rock operas and concept albums included, was challenging and innovative. But he worked for years to achieve what he did while many of his contemporaries came and went in the blink of an eye. Singers and songwriters of the same breed as Mr Townshend, artists unafraid to ignore trends and step outside the mainstream (if that’s what’s in their blood), and to do so time and time again would be the ones more likely to access the credibility he sought for their collective calling.

As for Countdown’s Mr X, that pop artist of the non-mainstream … perhaps he had just the one exceptional song in his arsenal. If so, the fact need not rob it – or rob any artist in the same position as him – of its power.