You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

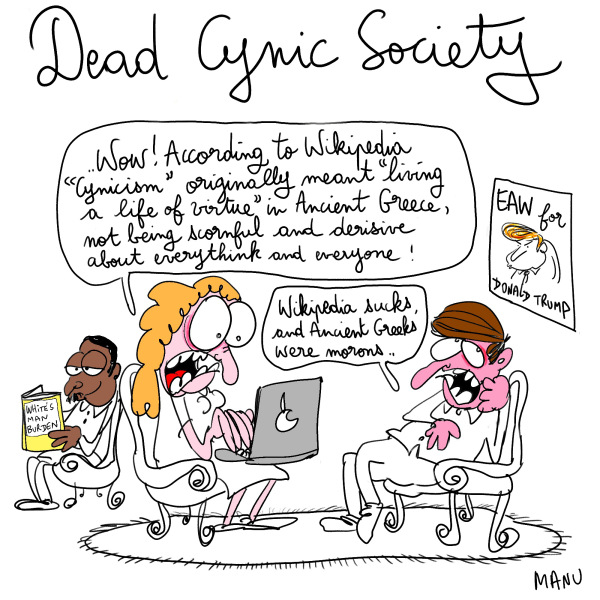

Are we a society of loyal sceptics? Those who believe you must gain certainty and security in a hazardous world that you just cannot trust.

This might explain, why there is an attraction, to fairy tales that lean towards the darker aspects of life and human existence.

Originally, fairytales held a mirror to life for adults through a medium of fable, imagination, easily relatable motifs and a core simplicity that hid layers of darkness (more often than not violent and tragic) and observations on people and society.

Maybe it is no surprise then that even now on modern re-workings of the most common fairytales –the motifs are children – where else do you find such a compelling blend of fantasy and hard reality.

We revisit the 2012 short story collection Sweet Home by Carys Bray, to find out.The title story is a modern-day version of Hansel and Gretel (with foreign prejudice thrown in to reflect modern society’s fear of the unknown), the rest of the collection show evidence of the influence of the fairy tale tradition.

In some, it is more obvious than the others as they are retellings of other famous folklore (‘The Ice Baby’ for example), but even in the others, there is more than a hint of whimsy, of a strong imagination, references to fairytales and a seemingly normal situation hiding a lot of darkness, pain and regret along with some universal truths.

In ‘The Baby Aisle’, a woman contemplates buying special-offer babies at Tesco. It opens with a normal narrative about a mother shopping for groceries. The surreal soon sets in as she talks about the baby aisle and how she arms herself with a list of things to buy so that she to not be careless like the previous four times. Most of the story takes place in the supermarket as the narrator battles her temptations. In the final scene, the mother (and writer) like a magician uses the pretense of a wholesome family as misdirection for the final reveal (“they sat around the dining table as good families should, she stocked the conversation with improved attentiveness, and longer-lasting laughter …”).

Throughout the collection, the image that we have of perfect, happy families (home sweet home) is reconstructed by the author for a much more realistic often sinister one. In ‘I Will never disappoint my Children’, we encounter a mother who finds herself in the very situation she had vowed never to be – disappointing her children. A painful childhood memory of Blackpool and ice cream is unconsciously repeated, and a feeling the narrator’s originally good intentions have been turned against her by circumstance. It is a retrospective regret as she realizes a minute too late – both the present and past narratives running parallel with the narrator’s young resolution as the closing line.

There are however plenty of instances in life where good intentions do turn out the way we had planned. We our rewarded with just that in ‘Love: Terms and Conditions’. In this story, the narrator is a woman whose parents always meted out their love and affection based on the certain rules, the adherence to certain conditions. The opening line sets the scene – “The photograph in my parents’ hall is a lie, a counterfeit memory they forged when I was small”. The photograph (of her as a bundled up 5 year old who wasn’t really allowed to play in the snow) is mentioned in the first line because the memory associated with it is key to understanding her desperate need to be a different kind of parent.

At a Christmas dinner with her parents, she and her husband have to prep their three kids about how to behave. While they are polite and perfectly nice, they are completely oblivious to how they are being perceived through the eyes of their grandparents whose affection remains measured. Later that night the mother builds her first ever snowman and revels in “snow angels and cold, damp happiness”. Not only that, but she decides to wake up her reluctant, sleepy children in the middle of the night so they can roll around in the snow. The next day her kids start a conversation where they ask her who her favourite child is. She realizes that each of her children is her favourite, that she loves them equally for their unique qualities and because “they are not like her”. Here the narrator has her own unsaid childhood promise of unconditional love fulfilled – and we are all the better for it.

But what if you think your love is not enough? That you are not adequate? The narrator in ‘Wooden Mum’ is looking after a young son with Asperger’s and constantly doubting whether she is being a good mother – even though she was the happiest woman in the world after his birth, “too happy to smile for fear of it leaking out of her mouth like a puncture”. This story is full of lasting images: Tom’s neatly ordered cars and what that symbolises for the narrator, the wooden mum doll figure with a gory red biro smile drawn on by her daughter, Letty, sweet-wrapper twist smiles.

Memories like the one above are rare, but even the ‘ordinary’ ones can be tricky enough. Especially our earliest. How many of our childhood memories do we really remember as they happened? We may not be consciously picking and choosing but there is a natural tendency to hold on to the highs and lows to create a sort of history about our youngest selves.

In ‘Dancing in the Kitchen’, a mother wishes she could cut out all the scoldings, disappointments, regrets and create memories of a patient, loving mother who was always just right.

Therefore, she starts to plan a perfect memory, one that involves music, love, laughter and a mother dancing in the kitchen. But in the end as she progresses from take one to the director’s cut, we can see reality setting in and the inevitable acceptance of her son having the “final-cut” editing privileges.

The final story of the collection appears to be a similarly bittersweet narrative but earns its happy-ending, however ephemeral. It is a “passing the baton” story where five strangers interact with one another in a sort of chain at the end of a school day. All of these strangers have some bruises (physical or mental or both) and in their interaction with each other, Carys Bray beautifully brings out their different characters. In this very brief story, we share in their sorrows and fleeting moments of peace.

At the core of the collection of stories in Sweet Home are stories that wear their emotions on their sleeves.

Each one is proud to admit the need for hope, imagination and laughter to understand the world with all its hardships.

Indeed children are-used as motifs for that very purpose. They bring a certain levity to the narratives, a world view that is frank and innocent – as precious and pure as it is heart-breaking in the knowledge that most likely somewhere down the road, the real world will interfere.

About Anushree Nande

Anushree Nande is a Mumbai-based writer, editor, proofreader with MA & BA Creative Writing degrees from Edge Hill University. She has published short stories and poems, and also writes about football, books, movies, TV for many websites, blogs and literary magazines. A first novel and micro-fiction collection are in progress.