You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

A memorable incident occurred on the set of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). Sam Peckinpah was filming a long shot of Bob Dylan walking down the street and noticed something bizarre: the singer had inexplicably changed hats between takes. The famously bellicose Peckinpah would not stand for this continuity error and so halted the filming. “Stop! Cut!” he said, remonstrating with Dylan about this change of headwear. “Yeah,” said a nonchalant Dylan. “I went inside and I changed hat… I want to have this different hat.” Eventually Dylan gave in, but his behaviour puzzled co-star James Coburn. “Bobby would go through all these strange machinations in order to wear different things. I don’t know why, to draw attention to himself or something.”

The anecdote is particularly fitting, as Dylan is the definition of the man of many hats. He’s worn the train-hopping hobo hat, the protest singer hat, the electrified iconoclast hat, the anguished divorcé hat, the born-again Christian hat, even the Santa Claus hat (or cap) – a mutability memorably captured in Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There (2007). His elusive shape-shifting has also expressed itself across media: the musician hat, the actor hat, the poet hat, the painter hat. However, there’s one hat which has remained on at all times, one which Face Value, his latest exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, throws into relief: the troll hat.

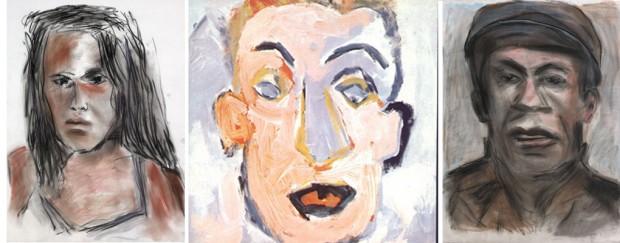

Needless to say, Dylan is not merely a troll. To say so would be scandalously reductionist; he, of course, contains multitudes. Nevertheless, he has long possessed the troll’s aptitude for provocation, mind games and deliberate absurdity. Face Value, a collection of twelve rough portraits of American misfits and nighthawks, harks back to the biggest act of trolling of them all: his 1970 double album Self Portrait. The LP – a sprawling assembly of sloppy cover versions and poor live recordings that famously prompted Greil Marcus to ask, “What is this shit?” – was Dylan’s attempt to distance himself from the earnest hippies who believed he spoke for them. Even before fans removed the disc from the sleeve its anarchic folly was clear, for it was the album cover that sealed the mission’s success. A comical self-portrait by Dylan himself – yes, it was also an experiment in literal humour – it was purposefully primitive, a crude and blobby medley of wacky eyebrows, protruding ears and a cherry mouth. The joke was that an album with a title as candid as Self-Portrait shod no light on Dylan’s identity at all: the songs were largely covers of other people’s; the silly album art bore little resemblance to the iconic photos by Barry Feinstein.

Face Value, more than forty years later, continues in this spirit. The portraits’ punning titles display a similarly mischievous humour – Face Facts, Face Off, On the Face of It, etc – and this playfulness itself explodes the exhibition title; only a fool would take Face Value at face value. Even the small size of the exhibition seems like an act of trolling: consisting of one three-walled room with four paintings on each wall, its scale is completely disproportionate to the publicity it has generated. As for the portraits, their slightly childlike simplicity cocks a snook at the elaborate contemporary portraits just outside by artists like Ishbel Myerscough and Justin Mortimer. The subjects of the pastel portraits are also consciously mysterious; Dylan has been open about mixing the real with the imagined, and visitors are left to guess whether the dapper “Ivan Steinbeck” or the muscular “Red Flanagan” are products of the singer’s imagination.

Not that it matters. Dylan loves to tempt spectators into overanalysis and then frustrate them, an impulse that becomes clear in the Q&A in the accompanying catalogue with John Elderfield, former Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art. Elderfield’s extended and thoughtful answers are met with terse rejoinders. When he asks whether the portraits’ “out-of-focus quality” is meant to evoke the subjects’ “shadowy existence”, Dylan replies: “That’s the type of pastel I was using.” When he asks whether the white space or “generalised tonal plane” in the subjects’ background is a homage to passport photos or photo booths, Dylan replies: “I haven’t seen any passport or photo booth photos in a while so I don’t know.”

None of this is to say that the portraits are terrible; they are certainly on a different plane to the wilful coarseness of the Self-Portrait sleeve, and I have little time for critics’ snooty hostility to musicians who expand into the visual arts. For all their roughness, the works are firmly in the delicious hardboiled noir tradition; the backdrops may indeed be a white space or generalised tonal plane, but it’s no leap of the imagination to picture a roadside diner or a backroom boxing ring.

At the same time, there is no doubt that, if the portraits were not by Bob Dylan, they would not be anywhere near the National Portrait Gallery. However, Dylan patently knows this and is having a whale of a time. Many enthusiasts have gone over the top in their praise, such as The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones when he described the portraits as a manifestation of “the poet’s unique vision” – but the exhibition’s detractors have, if anything, made even more of a fool of themselves in their po-faced outrage at the portraits’ crudity. After all, Dylan, in Face Value, is holding tightly onto his troll hat. He knows that Bobcats will try to connect the dots between the twelve portraits and the motley cast of songs such as “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” and “Desolation Row”; he knows that critics will drill for clues as to what makes the elusive troubadour tick. To subject them to scholarly scrutiny, though, only misses the mark, for they are simply the doodles of a man having fun with his mythology – and, enjoyed on this level, they work.

The portraits in Face Value, like Self-Portrait, refuse to elucidate anything at all, let alone any aspect of Dylan’s unstable identity. In viewing the exhibition, one Dylan quote in particular came to mind, a quote that exhibits a similar approach towards questions of identity: at once flippant and sufficiently mysterious to invite reams of analysis. In his Rolling Stone interview to promote his film Renaldo and Clara – itself a four-hour trollfest – the interviewer, Jonathan Cott, asked him whether his song “Is Your Love In Vain?” was autobiographical. “You could say that the song isn’t necessarily about you, yet some people think that you’re singing about yourself and your needs.” Dylan’s sphinx-like response? “Yeah, well, I’m everybody anyway.”

Bob Dylan: Face Value continues at the National Portrait Gallery until January 5. Menawhile, Bob Dylan’s new sculpture exhibition, Mood Swings, will be displayed at the Halcyon Gallery until Jan 25.

About Daniel Marc Janes

Daniel joined Litro in July 2013. He has previously contributed to the LA Review of Books, Little White Lies, the London Review of Books blog and the New Statesman's Cultural Capital.