You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

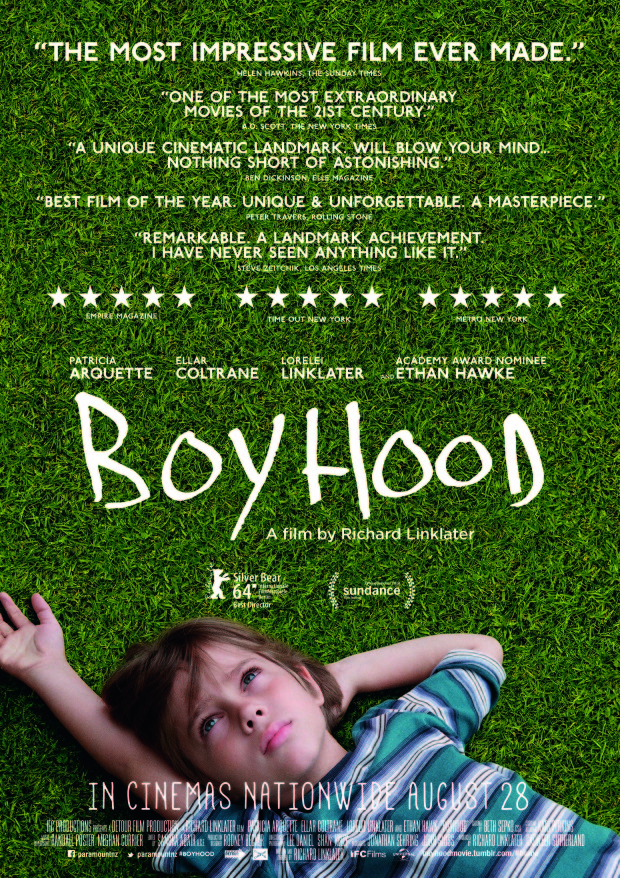

Go shoppingWith the Oscars well behind us and early frontrunner Boyhood left clutching just one award, it is worth revisiting the film and asking why it worked for some, and why it left others feeling a little empty.

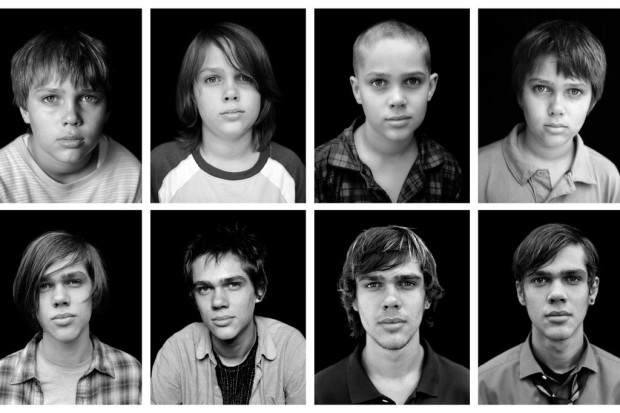

For those unfamiliar with the low-key saga, Boyhood is the story of 12 years in the life of Mason Jr (Ellar Coltrane), a diffident, slightly gawky kid growing up with his single mother (Arquette) and older sister (director Linklater’s daughter Lorelei) in suburban Texas. His father (Hawke) appears on the occasional weekend. A series of inadequate men pop up to replace dad and then vanish in due course. The kids go to school, the mother works and studies. They all do their best to get by. And of course time is conveyed as few films have conveyed it, the years bleeding into one another without ceremony, the actors growing or wrinkling across 12 actual years of production.

If you speak to people who don’t like Boyhood, a familiar lament seems to be that nothing really happens. The film just moves, people weave in and out of it, and the plot never hits, if indeed there is a plot at all. But this misses the point. Like life, the film is formless, an amoeba. It is full of little things, but nothing monumental. The people in it exist not for some existential purpose, but because birth compels them to do so. Correspondingly, there is no real direction, except towards greater age.

This is the problem. Some people look to cinema for escapism, for comfort. They go to the movies so that for a few hours they can see life in high-definition, full of villains, full of heroism, full of meaning. Boyhood doesn’t offer that. Instead it inverts the camera, and points it right back at you. Much great art does this, and perhaps cinema’s enduring popularity in part comes from the fact that it has often provided a respite from such heaviness. Boyhood shuns such light relief.

Towards the end of the film, Mason Jr’s mother Olivia begins to cry as her son packs his bags for college. She explains that her life seems to have been just a series of milestones: getting married, having kids, getting divorced, getting a degree and now seeing the kids who started it all off leave for college. Next is death. We try to ennoble these moments with bottles of champagne and balloons, but something seems to be missing. In response to Mason’s shrug, Olivia finishes with: “I just thought there would be more.” And then Mason Jr drives off into the sunset, a future of his own to carve out, moment by moment.

Boyhood recognises that being born posits a question: why? And no one can duck it. Sometimes events make the question vivid for a moment, as when a mother sees her son walk through the door to college, as blasé as if he was strolling to the shop to buy a pint of milk. Or when Mason Jr experiences rejection for the first time, his high school girlfriend tiring of his morose musings on the futility of everything and ditching him for the local lacrosse star. Mother and son stop and look for answers, but Boyhood has the integrity to offer none in response. As Mason Sr, the kind, vaguely feckless father, puts it when his son asks him what the point of everything is: “Everything? I sure as shit don’t know. Neither does anyone else. We’re all just winging it.” Indeed.

After he read War and Peace, the Russian journalist and writer Isaac Babel said: “If life could write, it would write like Tolstoy.” You can’t get much higher praise than that. Boyhood may not have the magisterial scope of War and Peace, and the safe suburban world it charts provides material less epic than the Napoleonic Wars, but Babel’s words apply to it as well. And by presenting life on screen, with all its little events and its big question, it transforms it into art and gives it some nobility and beauty, which is the best we can hope for.

At close to three hours, this is a long film – but like the subject it charts, it goes by all too quickly. Who knows if it was the film of the year or not. Perhaps that depends on what you go to the movies for. But people should go to see it, because whoever they are, it is about them. It is about us.

About Harry Waight

Harry Waight is in his twenties, and spent his youth travelling around the world in pursuit of his parents. He returned to England to study history at university. He currently lives in London, plotting to escape again. In the meantime, he enjoys writing about things he has read, watched or heard.