You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

You might recognise the following scenario: a photo or video appears on a social media site – say, Facebook or Twitter – and catches your eye as you scroll through a blur of familiar faces. It shows an atrocity, someone or something full of pain, and it asks that you pay it attention. You, naturally, are horrified and hurt by this other being’s suffering, so you click “like” or you retweet, and you feel a bit better. You have done your part and a vague sense of self-satisfaction settles over you.

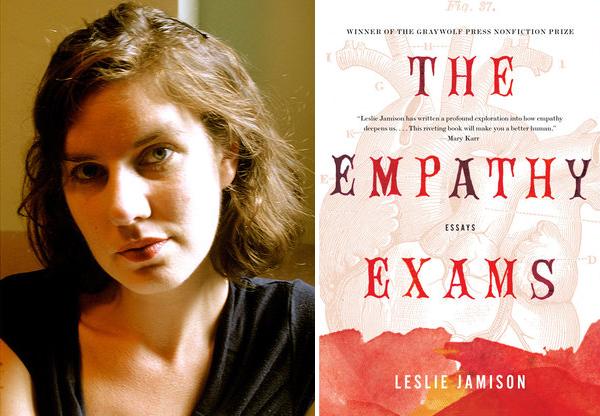

This, says Leslie Jamison, is one of the perils of empathy: the “concluding note of self-satisfaction” that comes after a response to another’s pain, a kind of emotional hollowness. For, she argues, what is the use of empathetic pats on the back if there is no real investment behind the feeling? But if this sounds like Leslie Jamison has a negative attitude towards empathy – and its sisters sentimentality, vulnerability, self-exposure, confession, guilt and self-examination – then nothing could be further from the truth. In both her new title The Empathy Exams and in conversation with Olivia Laing on July 8 at the London Review Book Shop, she eloquently, intelligently and convincingly puts forward the case for empathy in most of its guises.

Her first essay, and easily the most personal and self-exposing, is one in which she examines, unnervingly honestly, the abortion she had while she was working as a medical actor playing out other people’s pain – a moment of extreme vulnerability and pain making her think how she wanted other people to regard her in that moment. How we react to other people’s pain and how we hope people react to our pain is never more complex, she points out, than in women, who are overly self-conscious of the image of “the suffering woman” as an outmoded model for female pain. In particular, women, she argues, are inclined to use irony to distance themselves from feeling – a “post-wounded” ironic relationship of sorts.

Why is it that people shy away from pain – from confessing it, sharing it, viewing it – and consider many of empathy’s traits to be vulgar, voyeuristic or overly sentimental? There is no doubt that this is writing and talk that is easy to attack as solipsistic or feel squeamish about, about which it is easy to say “what’s the point?” – but Leslie Jamison and Olivia Laing deftly undercut these arguments with a bold assertion of the value of empathy. And not just empathy in the broad sense that most of us see as valuable – an understanding of other people’s suffering – but also empathy in its less attractive guises: sentimentality, for example.

In what Oscar Wilde deemed “the luxury of an emotion without paying for it”, there is a kind of shallowness – all the uncomplicated sweetness of an instant feeling without any cost. Leslie Jamison sees value in sentimentality, however, if it provokes awareness – if it, so to speak, sets off a chain of emotions, a kind of “chronology of experience” that leads to better understanding. She has an admirable faith in the process of feelings, that one feeling, not necessary “useful” in itself can take you to another, valuable emotion.

And it was here that Jamison and Laing’s conversation took on an unexpected angle – and began to consider the potential social and moral payoff of witnessing a pain. One of Jamison’s essays concerns the case of the West Memphis Three and the Paradise Lost documentaries that presented multiple and challenging claims to the viewer’s empathy – whether for the victims or the defendants – but which, by drawing attention to the case, played a part in the defendants’ eventual release from prison. In the same way that empathy can be used as a tool to raise awareness, so too can confessional writing be used to increase understanding of experiences, both personal and alien. A book, a piece of writing, is not an autonomous unit, Jamison argues – and, as such, a confessional piece of writing can spark a conversation with a reader, it can make someone feel less alone, it can comfort. There is value, here, again.

It is hard to accept all of Jamison’s arguments – not least because our own, deeply entrenched, prudishness might dismiss them as self-indulgent. It’s a fine line to tread, but Jamison treads it well, showing an impressive and scrupulous commitment to self-examination. Warm, humorous, eloquent, intelligent and precise, Leslie Jamison offers both complexity of thinking and accessibility of expression – it’s the kind of conversation and knowledge that demands more attention than a simple click and pat on the back.

About Bella Bosworth

Bella Whittington reads and reviews a bit of everything, but is particularly interested in literary fiction, translations and short stories. After living in Spain for a year, she now works as an assistant editor for Transworld Publishers in London. She has also contributed to Thresholds, the University of Chichester's international short story forum, and the Harker.