You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Has the genre of the Great American Novel died out? Genre, in the end, is not much more than a system of drawers we use to file away short stories or memoirs, essays or poems. In times of crisis, those drawers start to rattle and crack in order to give way for a writing that envisages change. The grand narrative of American literary history, though, seems built around a different idea. In 1868, shortly after the Civil War when the USA was still very much in emergence, John William DeForest first coined the term that was to become the holy grail of US American writing. “The Great American Novel,” he opined, would chronicle “the ordinary emotions and manners of American existence,” thus containing crisis and framing it in the tight, tangible binding of a book. It can hardly surprise, therefore, that a search is already underway for the writer that can adequately respond to today’s troubled times. Candidates include Donald Trump himself: Newsweek’s Alexander Nazaryan reads, with bitter irony, the president’s tweets as a serialized GAN of the fall and rise of the American nation; on the other side of the spectrum, Aaron Bady suggests Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers, an immigrant story deeply ambivalent about the project of being, and becoming, American.

Has the genre of the Great American Novel died out? Genre, in the end, is not much more than a system of drawers we use to file away short stories or memoirs, essays or poems. In times of crisis, those drawers start to rattle and crack in order to give way for a writing that envisages change. The grand narrative of American literary history, though, seems built around a different idea. In 1868, shortly after the Civil War when the USA was still very much in emergence, John William DeForest first coined the term that was to become the holy grail of US American writing. “The Great American Novel,” he opined, would chronicle “the ordinary emotions and manners of American existence,” thus containing crisis and framing it in the tight, tangible binding of a book. It can hardly surprise, therefore, that a search is already underway for the writer that can adequately respond to today’s troubled times. Candidates include Donald Trump himself: Newsweek’s Alexander Nazaryan reads, with bitter irony, the president’s tweets as a serialized GAN of the fall and rise of the American nation; on the other side of the spectrum, Aaron Bady suggests Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers, an immigrant story deeply ambivalent about the project of being, and becoming, American.

For me, a German researcher of American literature, the idea of a great American novel has always been a guilty pleasure. The belief that there could be an all-encompassing novel out there just seems too pre-lapsarian to be true, whether it would explain the forces that keep the world turning, or the powers wanting to see it burn. The world, after all, tends to resist being swathed in formulae. Nevertheless, the fascination with the great American novel persists and makes it the Michael Jackson of the literary world. The appeal is clear: a literary synthesizer, akin to the dancer’s steps that lit up the very ground he walked on, illuminating the confusing darkness of US-American reality.

Yet this has always been more about the search than the destination, and I wager a prediction: once again, the definitive American masterwork will remain either an unfulfilled dream or a never-materialised nightmare, depending on where you stand in this debate. This is not because of a dearth of talented writers, or of a lack of interest in the current zeitgeist, quite to the contrary. Paradoxically, the era of a president famously disinterested in all matters literary has seen the media turning to authors as interlocutors about current events. This is true, too, for the general public who is rediscovering the dystopian visions of George Orwell as a guide to a country many feel they don’t recognize any longer. This testifies to the fact that new modes of thinking are called for in the face of a nationalist upsurge that is anything but new, but which remained under the radar for too long. And as the data-based models of the polls failed to register this upheaval, geared as they are towards familiar patterns rather than to the emotional force field of anger, it is not without irony that literary writing becomes a poignantly relevant mode of thought in a post-truth age.

The Great American Novel, however, is doomed to failure not because literary writing has lost its bite. It is the politics involved that mark its downfall. Much as I enjoy the debates about whether DeForest was right to exclude The Scarlet Letter from his own list, I have never been able to shake off the nagging feeling that there is something uncomfortably authoritarian in the idea of a grand narrative. It is no coincidence, after all, that DeForest links the Great American Novel to an age in which democracy has not yet taken hold. My own innate suspicion that darkness inevitably accompanies the tantalizing pull of greatness has been nurtured by growing up in the shadow of National Socialism. Not that indulging the fantasy of an all-encompassing narrative as such is wrong. But now that American greatness, fuelled by the “red blood of patriotism,” seems to channel the darkest side of European nationalism, perhaps it is time to approach the great American novel with similar caution. There is nothing particularly democratic about the idea of a magisterial vision, literary or otherwise. The sense of crisis warrants a different narrative shape.

In the face of the authoritarianism and nationalism of the Trump government, it is time to replace the search for the Great American Novel with a journey towards a literature that counters dominance. Interestingly, an often overlooked line in DeForest’s essay offers support for this project: “ We may be confident that the Great American Poem will not be written, no matter what genius attempts it, until democracy, the idea of our day and nation and race, has agonized and conquered through centuries, and made its work secure.” If we follow this line of thought, this puts us in an in-between state: between the novelistic, which DeForest equates with a pre-democratic state, and the poetic, the securely democratic condition. Genre is the textual shape we expect our experience to take, and in this sense, our experience is a decidedly hybrid one: of a democracy that is in upheaval.

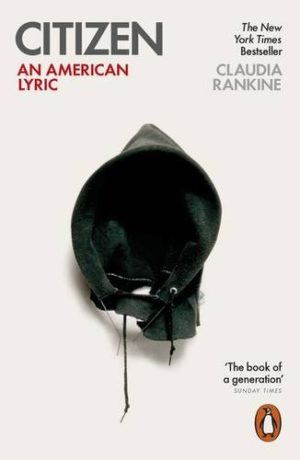

Instead of magisterial masterstrokes, it is time for a writing of ferocious precariousness. After all, the very idea of ordinariness that underlies DeForest’s idea of a literary kaleidoscope of every-day American’s emotions has been whitewashed by Trump’s discourse of the ‘American People.’ To capture the meaning of being American today, literature needs to refuse to give credence to this nationalist narrative. Claudia Rankine, for instance, re-writes citizenship in response to those who are being implicitly and explicitly excluded: “Call out to them. I don’t see them. Call out anyway. Did you see their faces?” And she does so in texts that do not fit into any of the drawers of our genre categories. While Trump constructs a perverted narrative of national greatness, she exposes the moments of rupture when systemic racism breaks through the surface of 21st-century realities.

In this new incarnation of the Great American non-novel, universality is not the point. The point is breaking the sheen of misperceptions and appearances. This is the Democratic genre of our time. Not the texts of greatness, but of living democracy. A re-written history of the Great American Disobedient Prose, therefore, might include not The Great Gatsby or The Catcher in the Rye, but Douglas Kearney’s mess poetics, Claudia Rankine’s thinking “as if trying to weep,” and Lyn Hejinian’s rejection of closure. It would be much harder to pin down and to summarize on sparknotes. But it might just give us the kind of thinking that is needed today.

About Katharina Donn

Katharina Donn’s first book, A Poetics of Trauma after 9/11", has been published by Routledge in 2016. She works internationally, between Germany and London, and is employed as associate lecturer and post-doctoral research fellow at the American Studies Department at the University of Augsburg. She has also held positions with the University of Texas at Austin and with the Institute of Advanced Studies at UCL. She enjoys being a transnational traveller, commuting between Germany and the UK, and works with the Brilliant Club at London state schools to advocate equality in education.