You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingForce Majeure (originally titled Turist) by Swedish director Ruben Östlund is like a Caspar David Friedrich painting inhabited by characters from a Michael Haneke film: the stark yet sweeping Romanticism of the French Alps is a counterpoint to the vanity and shallowness of a bourgeois family on a skiing holiday. Their neon ski garb and their civilized manners are no protection against the forces of nature, which ultimately shatter their fragile cocoon. On day one of their holiday, Tomas (Johannes Bah Kuhnke), Ebba (Lisa Loven Kongsli) and their two gorgeous children, Vera and Harry (real-life siblings Clara and Vincent Wettergren), are photographed on the slopes by the resident photographer. In their body language we sense immediately that something is amiss: the strained smiles, and the awkwardness as the photographer asks Tomas to put his arm around Ebba.

Our feelings of unease are further heightened by the mise en scène: barren, crisp white mountains, sterile tunnels connecting ski runs and empty chugging chair lifts recall The Shining more than Ski School. Vivaldi’s almost manic Summer segment from his Four Seasons soars over images of the resort and its incessant snow-making machines. Ominous canon fire, used to create controlled avalanches, also punctures any ease on the viewer’s part. We are firmly on European art-house terrain, and stunning it is, too.

The ski resort’s sleek blond wood interiors and the photogenic family lazing in their matching long underwear self-consciously parody the world of advertising. Yet from the first moment we meet them, we know that under this veneer of middle-class life lie some very deep flaws just waiting to be explored. And Östlund does just this. He forensically exposes the cracks in this relationship just as his compatriot Ingmar Bergman did in Scenes from A Marriage. In this case, Östlund puts the couple in danger. He asks: How will they react when they are torn from their normal day-to-day mode and forced into survival mode? And the film itself answers this question: Not very well.

This danger arrives in the form of a controlled avalanche, which appears to go awry, and threatens to engulf the family along with dozens of other tourists while they eat lunch on an outdoor terrace. We watch as the avalanche goes from a sight to be captured on every iPhone, to something that is getting a bit too close, to a seemingly catastrophic event as everyone either runs for cover or dives under tables. It is beautifully shot, using footage of a real avalanche in British Columbia, a large green screen on set in Gothenburg and real smoke to look like snow. As Östlund has said in interviews, he wanted to create the most spectacular avalanche sequence in film history.

The formal rigour with which Östlund has lead us though this terrain is then echoed in the controlled dynamic between the central couple. Control is an underlying theme throughout the film, with Tomas and Ebba trying vainly to stem their reactions to the avalanche. The landscape has its wildness tamed by being reduced to manicured mountains covered in manufactured snow and yet one feels at any moment it might rebel. To Östlund, this parallels human emotions, which like nature are also not to be controlled. The marriage portrayed in this film, like the mountains in the background, is rife with fissures that have the potential to engulf the members of the family at any moment. Despite willing themselves back to normality after their near catastrophe, the characters have revealed themselves to be what they are: Tomas is the sort of man who runs away from his family, grabbing his phone on the way; while Ebba stays put and tries to protect their children. For the rest of the film Ebba tries to reconcile what she sees as her husband’s deep cowardice with the man she thought he was. Her frustration, which she tries to keep under wraps simmers up when she and Tomas are with other couples. These excruciating scenes of public humiliation and domestic unravelings make for some of the best moments in the film. Ebba displays the icy beauty of a Bergman actress, particularly that of Ingrid Thulin (Cries and Whispers, The Silence). She is an actor who quietly watches, and without a word manages to convey her every thought. Kuhnke’s performance expresses something creepier. He is not an innocent and even his tears, it turns out, are fake.

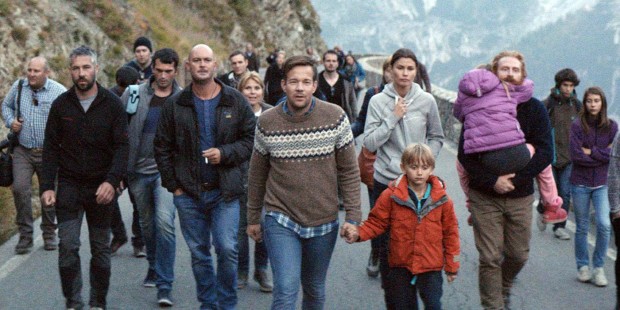

Unfortunately, what is played out after the moment of danger, whilst insightful and gripping, seems to then escape the director’s control. The film’s inscrutable logic falls away. It is all the more noticeable because the first two thirds of the film are so perfectly water tight. This is a film in search of an ending, and Östlund can’t seem to settle on one. When the family leaves the resort, we see them on a bus with other holiday-makers. The driver incompetently lurches around hairpin bends narrowly avoiding sheer drops. Ebba, in a panic, insists that the driver let her off. She doesn’t take the children with her. She commits the same crime of which she rightly accuses Tomas. Yet, it is not clear what the director is saying here. Are we to believe that because the danger in this case is simply perceived by Ebba and not necessarily real, it is acceptable for her to flee, leaving the children behind? Or are we to questions the idea that there is one set of rules for a woman and another for a man? I was baffled. Just as I was baffled by what comes next. The passengers file off the bus and do a sort of Nights of Cabiria-style ponderous walk. Tomas lights up a cigarette and comes clean to his family about being a smoker: gone are the pretences. Now that they have seen themselves nakedly for what they are — she: neurotic and prone to publically shaming her husband and he: cowardly, unfaithful and manipulative — they can finally let it all hang out. Then the camera lands on the young Fanni (Fanni Metelius), who we know from previous scenes is having an affair with a much older married man, Mats (Kristofer Hivju). Is the director trying to convey in this shot, that the mess of relationships is destined to live on in future couplings? Is he making the point that we all start off thinking we will be different, as do Fanni and Mats, that our marriages and relationships will be pure an untainted by the darker forces that lurk within us only to be proven wrong when our flaws eventually surface? That, ultimately, it is impossible to keep our natures under control? I wasn’t sure. Yet, the point of a good work of art is not to come to any hard and fast certainties but to get us probing and thinking about what these certainties might be. And Force Majeure does this brilliantly.

Force Majeure is in UK cinemas from April 10th.

About Joanna Pocock

Joanna Pocock graduated with distinction from the Creative Writing MA at Bath Spa University. She is a contributing travel writer for The LA Times, and has had work published in The Nation, Orion, JSTOR Daily, Distinctly Montana, the London Sunday Independent, 3:AM, Mslexia, the Dark Mountain blog and Good Housekeeping, among other publications. In 2017 she was shortlisted for the Barry Lopez Creative Non-fiction Prize and in 2018 she won the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. 'Surrender', her book about rewilders, nomads and ecosexuals in the American West, will be published by Fitzcarraldo in 2019. She teaches Creative Writing, both fiction and non-fiction, at Central St Martins in London. Some of her writing can be found at: www.joannapocock.blogspot.co.uk and www.missoulabound.worpress.com