You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

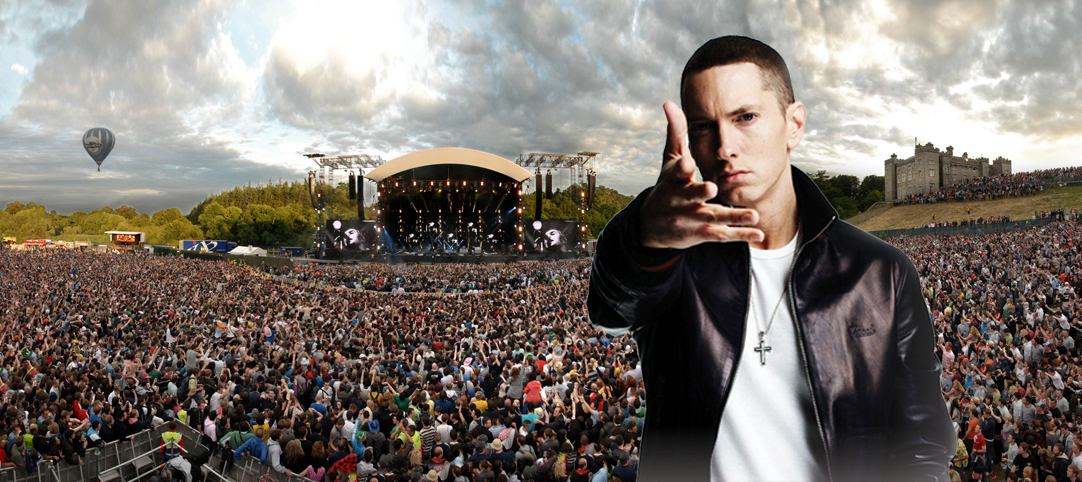

In a moment of bravura just before Christmas last year, I bought my husband tickets to go and see Eminem at Slane Castle, 40 miles outside Dublin. We are not yet 50, but it won’t be long, and we’d never been to a big gig before. Ever. And it was Eminem. Eyebrows have been raised. Despite my husband’s passion for classical music and opera (he took me to see Tosca in Rome a few weeks ago), he’s been an Eminem fan for a decade, admired his searing satire, the savage energy of his take on contemporary America.

As we drive the five hours to Slane from Cork we listen to Curtain Call, a greatest hits collection, the only Eminem album I could find in Cork on Christmas Eve last year. The first track is (as Eminem says) “a song for da ladies”. It’s a difficult listen – a violent parody of female sexual desire. When my husband starts to play his Christmas present last year, I hastily turn it off, lest the children be lulled from their Lego frenzy and notice what’s being said. But I’d also protect them from a whole gamut of art that treads the ground of violence, sexual abuse and racial or sexual prejudice – not because I necessarily think it bad art, but because they are too young to appreciate the levels of parody and mimicry that are sometimes at play. It isn’t straightforward to interpret this work, to balance the pleasure of linguistic beat and rhythm with matters of political, sexual and social import – and yet I respect Eminem as an artist, believe him to be an original and important voice.

Other contemporary artists tread a similar terrain to Eminem, and while few have achieved his international profile, their work elicits a similar response. The American performance artist Karen Finley is one of them – her discourse of obscenity, her “fuck and shit vocabulary” (Carr 1986), has had her as the bad girl of contemporary performance art for a generation. Like Eminem, Finley is a searing performer, with the keening voice and delivery of a southern preacher, treading the terrain of abuse with a raw emotion that makes being at one of her performances something of a rite of passage. Finley infamously used foodstuffs on her naked body during her early performances, chocolate representing faeces being the most documented. What links Finley to Eminem is her playful and troubling occupation of contradictory positions. Watching archive footage of a Finley performance from the early 1980s, she is coquettish and giddy at its beginning, colluding with a rowdy club audience about the sexual frisson of her imminent nudity, but when she begins her aching text this changes utterly. Whatever it is this audience hears, it subdues them even from drunken heckling. This is difficult but important work. Annie Sprinkle’s 1990 ‘Public Cervix Announcement’ invited an audience in New York to view her cervix through a speculum; she would dress in a showgirl’s outfit and gently encourage spectators to look inside her body. This work went on to generate reams of feminist criticism in which the complexity of Sprinkle’s act was undone – the position of spectator assaulted, the peep show turned into a parody of overexposure.

Back in Slane we make our way through 80,000 people to listen to EarlWolf, the support act. We are “motherfuckin’ cunts” quite often, apparently, but it was unconvincing cursing, as if they knew you had to be bad-mouthing if you were into rap, but were mimicking it. Sort of like toddlers shouting “bum bum”. We don’t care too much though, because we are waiting for Eminem. While we do, I see more penises than I’d seen for a good few decades. Half a dozen pissed pissers, not bothering to turn their backs while they urinated, or right beside us showing their genitals to their mates with jokey cockiness. We might be motherfuckin’ cunts, but I seemed to be surrounded by dicks of all kind.

Eventually, once the light had gone and a moon appeared, and we could only dimly see the coastguard patrolling the River Boyne, Eminem came onstage. We are thrilled and grin at each other in the electric darkness. Eminem’s linguistic playfulness, his irony and his sheer musicality is a pleasure. But he doesn’t really connect to the audience at Slane, and instead uses his sidekick to do most of the talking. When he does speak to us, it’s an awkward collusion with his own experience. He asks: have any of us had trouble with our parents? And then we are to shout out “Fuck you Mum!” before he heads into “Cleaning Out My Closet”. Or we are to stick up our middle finger, as if we needed coaching in how to be really, really rude. It’s a bit like pantomime for grown-ups, and it doesn’t meet the sensibility of this young Irish crowd. But mostly his music makes us forgive him.

Once it’s over, and we head back up the hill with a small city of people at our shoulders, we get caught in a crush for the exit. These are fifteen frightening minutes where we can’t get out of the moving surge. We feel the pressure increasing, almost everyone is drunk, and I start yelling at people behind us not to push. There’s a helicopter overhead shining a spotlight on us and I’m gripping my husband’s arm and hand like I’m drowning. Once we are out of the squeeze and walking back along the same country lane after the concert, a car passes us full of young men, bearing a sticker that says “Four Doors For Four Whores”. We realise the danger of this terrain. I’ve been pressed close body to body with a thousand of these young men and women, but this doesn’t mean I can inhabit their insecurities, their easy politics of women as whores shoring up vulnerability, masked as violence. And the young woman photographed giving oral sex to two men inside the grounds of Slane, and subsequently sedated in hospital, is the cost.

About Jools Gilson

Jools Gilson is a writer and broadcaster based in Ireland. She was Director of the dance-theatre company half/angel for ten years, holds a PhD in Theatre & Performance Studies, and has taught performance and critical theory at the University of Hull and Dartington College of Arts. She currently teaches in the School of English at University College Cork, where she is the Associate Director of a new MA in Creative Writing.