You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In the few days before Christmas I ambled over to the Wellcome Collection to see their major winter exhibition, Death: a self-portrait. It features an enthralling collection assembled by Richard Harris, a collector who sought initially to explore the human anatomy through myriad icons, avatars and manifestations. Interestingly, early in his collecting, he had not realised how death would come to be such a leading theme in his pursuit of the human form. It is apt that, in the pursuit of depictions of the body and anatomy, as one looks closer and closer at life, the inevitability of death emerges. Any profound contemplation of the living world will also evoke the inevitable contrary. The more nature is explored the more it is shown to be as much about death as it is about life — a poignancy familiar to any viewer of wildlife documentaries.

The show is impressively diverse, featuring anatomical drawings, library plates and vernacular photographs alongside prints from familiar names in art history — such as Rembrandt, Dürer and Goya. More than providing an historical survey of the theme of death in art, the exhibition offers an account of how humans have aestheticised concepts and ideas of their own mortality. For example, as I wandered through the rooms I was treated to an eclectic array of art and cultural documentation. From Kawanabe Kyosai’s Frolicking Skeletons to Linda Connor’s photographs of culturally sacred sites in the Himalayas, via prints from Goya’s The Disasters of War series, the impression left is one of an impartial historical and global survey rather than an acutely directed inquiry.

One of the most resonating questions I was left pondering over was of representation. In many respects the contemplations of death, the associated images, the rituals and ceremonies built around the concept are all vicarious — somewhat removed from the morbid subject. As reflected in literature, philosophy, film and art, the thing that makes death so deathly is its distance, its unfathomable nature. It is perhaps because of this that it is such a consistently fruitful theme for the creative facets of culture — be it ceremony, art or ritual. I suppose that Death: A self-portrait is more accurately a portrait of creations. It is a survey of imaginative efforts to see something we don’t know. To consider, depict, portray or address the concept of death is always an act of imagining — regardless of whether the effort is cultural, documentational or artistic. Perhaps this is why the Wellcome Collection’s exhibition of art alongside cultural documentation, scientific curiosities and antiques is so attuned and composed.

Running through all parts of the exhibition is the dilemma of body and soul brought about by death. Almost every attempt to negotiate the concept of death has to traverse this dichotomy. Sometimes it is given a body of sorts, as seen in Ivo Saliger’s The Doctor, the Girl and Death and also Alfred Rethal’s Death the Friend. Here Death becomes cheapened as it is personified, or anthropomorphised. But these walking characters of death, whose cultural endpoint is no doubt the mundanely suburban stoner Death who mopes through Family Guy, are still removed from life. If Death is not shrouded in a cloak, it is a bare skeleton. And skeletons are uncommon sights in everyday life; they are quite unnatural things (culturally speaking) that go unseen for the most part. Ordinarily, we never know or see our skeletons, or those of our loved ones. Despite being our very core, like death, they are also removed from life as we are accustomed to seeing it. The skeleton in art is a stand-in, an avatar that is comfortably quite unlike our everyday experience of corporeality and life. It is a fiction that we cultivate. This idea of the skeleton is reflective of our lives and yet exists beyond it: like the traditional theological notion of a soul.

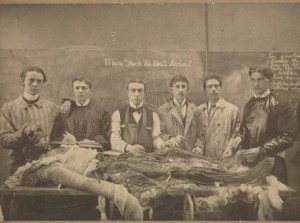

At the other end of the dilemma is the real, mortal human body, which seems insufficient to portray death — it is not quite deathly enough. When looking at 18th-century gelatin silver prints of doctors studying cadavers it is clear that death is out of reach. The body in the picture is too bodily; it is too of this life, making death feel even more of an impossible contemplation than the jolly dancing skeletons in the Dance of Death. All the pieces in this exhibition seem to fall on either one side or another of this problem: that the body is too lifelike for depicting death, and yet all other signifiers for death (masks, cloaked beings and skeletons) are not close enough to our bodies and our life for us to truly relate to it. In demonstrating this impossibility, this exhibition is strictly wonderful and shows the creative efforts that operate from each side of an eternal dilemma: the concept of death in itself remains elusive and impossible to fully conceive.

Despite the evasiveness of this eternal mystery the collection uncovers a bittersweet fact of life: it is about death as much as death is about life. The inspirational collection approaches death through the many diverse facts of living and humanity — body and soul. Love, war, science, art, dance, ceremony and learning are all major facets of life in the exhibition that, inevitably, also uncover death. It is in this sense that the exhibition uncovers the vitality of death.

Death: a self-portrait is exhibiting at the Wellcome Collection (183 Euston Rd, London NW1 2BE) until 24 February 2012.

About Tristam Vivian Adams

Tristam Vivian Adams is currently studying at Goldsmiths College. He blogs at notesfromthevomitorium.blogspot.co.uk.