You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

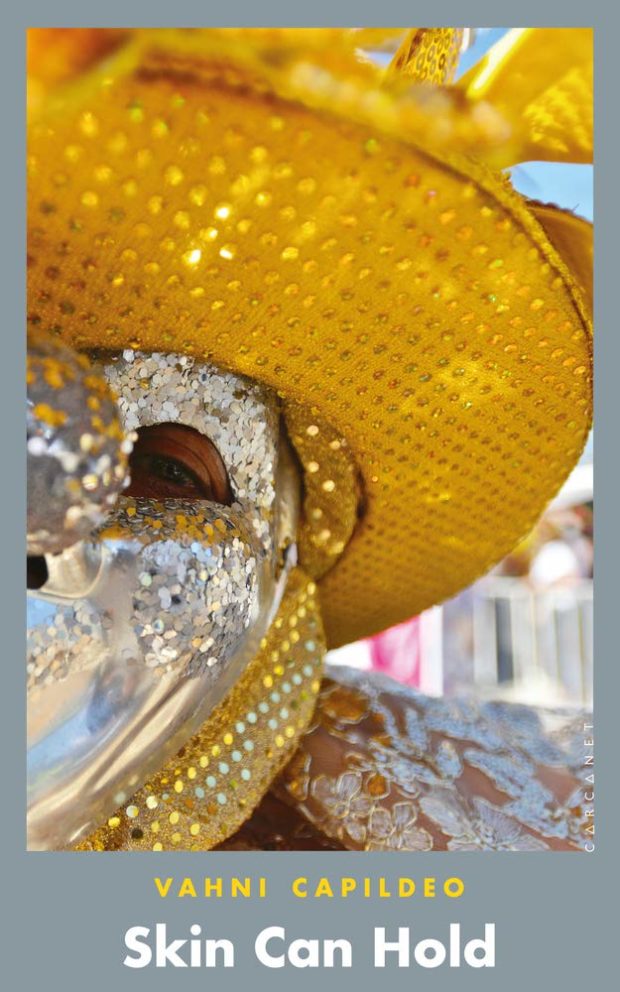

Vahni Capildeo’s Skin Can Hold bursts with ideas, electric with the joy of words. Capildeo is a writer enamoured with language, and her book offers up sextina, rondeau, motet, dialogue, oulipo game, just about everything you can imagine; her tone shifts in emotion too, from angry, to playful, to puzzled, to scholarly. “Panting, ending, burning, invading, weeping, / burning, caressing, longing! Reworking / thickens the trunk of the text,” she writes. Language becomes the source of everything: rapport, stultification, light-heartedness, violence. Grammar links to the body, and through such extreme love of language we discover new forms of love itself.

Already-existing forms of language can make us feel distanced or separated from intimate connection with others, so part of Capildeo’s task as a poet is “unpicking lexicons”. Her attention to language means she’s fascinated by advertisements and announcements, by the sounds of words, by onomatopoeia (“tapped, tripped, trapped”), by repetitive structures (“I come, I seize, I erase”), by languages other than English as well as the many varieties of English from regions of the United Kingdom, the Indian diaspora, the Caribbean and other ex-colonized territories.

Some of this interest derives from her own Trinidadian-Scottish background — we all start somewhere, before we open ourselves to the vastnesses that exist beyond the accident of immediate context. Some come from the places she’s lived, some from her linguistic training (she has a PhD in Anglo-Saxon Literature from Oxford and has worked as a lexicographer), some from friends, some from a realm of the imagination never before heard or seen on this planet.

Across her many collections, including Simple Complex Shapes, Measures of Expatriation, Seas and Trees and Venus as a Bear, Capildeo’s playfulness with language becomes a kind of resistance to forms of identity that insist on a supposed purity or authenticity. Her literature makes different sources clash, not only inhabiting but also creating new voices and traditions, producing associative-chains between sources that wouldn’t often come into contact in a single person, or in recorded History itself. Building another zone for linguistic play that’s hard to pin down in space and time is a never-ending project, since there’s forever “still more chaos effectively to organize”. But she does it, with wit and humour, as a master of parody, drawing out rhetoric a little farther than it tends to go, to demonstrate its flexibility or absurdity, for instance with bureaucratic directives: “Customers travelling with children must ensure that every child / travelling on the brown bag service is individually brown-bagged.”

There’s a similar movement at work in her performance instructions, which begin as more or less something to follow, and end in abstraction and interior space. Modern theatre often focuses more on evoking emotions than on movements of plot, but here words are distanced to the limit from possible interpretation: “He reads with the abstraction of a bichon frisé abandoned in the Hofgarten. You stoop, stretch, circle, segment, re-attach the relation of your body to the space around him.” The work contains its own critique, and mention of “an alternative version of this performance” occurs in the instructions themselves. Performance itself is less the point, maybe, than possibilities.

This section ends with the beginnings of language, as a girl, alone, sings vowels to herself: “No performance, such as untying ribbons to give to passersby, is involved.” The suggestion here is that engagement with others is itself a kind of performance, an idea that also appears in other poems. There are a few in the first person, notably “Shame”, about humilation of all kinds, sexual, professional, collateral, and so on: “The occurrence of the pretence as play; the occurrence of protest as pretend play; the performance of self-harm as protest: with its roots in the shade of the netted tree, this was shame (…) Shame on behalf of others is tiring. I hold it in the bowl of my pelvis, as empty as a night of timed-out stars. Shame on behalf of others flips into fury.”

But it would be a mistake to think of her as primarily an autobiographical poet. One of the things that fascinates me about Capildeo is precisely that she’s shifty, that her trompe l’oeil surfaces don’t say what you think they will, or at least not in that way. She’s a slippery fish who wriggles away from the reassuring poles of sociological discourse. Multiple times the idea of policing of literature comes up, for instance, as in her reflection on the “online angloamerican feminist group ‘protoform’” which cancelled several of its own, or her comment that “the frauds / claim exotic identities and needs”, an ambiguity that becomes interesting given how Capildeo is often herself positioned as a mouthpiece of this kind in the British poetic firmament.

Given her twin preoccupations with language and performance, it’s natural that when Capildeo finds her way to Shakespeare and other texts from the traditional canon of English literature, she juggles them into something new. Several poems list “sources” at the end of pieces, often combining a more classic work with something contemporary like Wikipedia. This incongruity might feel alienating or academic, and it’s true that many times I felt the texts gave me the slip, in a way they wouldn’t if I understood the original reference, or made the effort to study more. Isn’t that the modernist idea, I berate myself, that the poet makes demands of the reader, that she’s expected to capture the heady allusions?

Yet another part of me rebels against this, and claims my right to enjoy the poems without fully understanding them. I think Capildeo would like this, too. In a video for the University of York, she insists that the readers should pay attention to the pleasure of language for its own sake, and the ways it makes one want to write something of one’s own. And in her work on Martin Carter (which I’ll discuss further on), she writes: “Place ingrained in feeling seems to encourage researched reading. Sparse details can be unfurled into Guyanese realities. We, on the contrary, appreciated without wanting to dwell.”

The stage directions in “her” Shakespeares are, again, fascinating in how they serve to disorient as much as orient. As she says later in the book, “Directions arrive as if / translated from the more helpful souls / in Dante’s hell.” Shakespeare, like Capildeo herself, is agile as a carp and “alive, you type, and inconveniently alive in quick vertical, like on social media once, where a set of honest and original poets said no white actor should presume to play Othello since his is the only part black actors can without ripping the expensive delicate illusion of good theatre. I took by the throat these angels of the house, and clicked unlike”. Again, there’s no space here for saying what one can’t do, for invention will permit no red tape, closed signs, or boards laid in a forbidding “X” over locked doors.

Capildeo defends the idea of honestly and intimately metamorphosing into other bodies, minds, spaces and eras, to make hybrid creatures, greenhouse flowers and alien beings that you recognize in the mirror. The title of this poem, “Radical Shakespeare”, is perhaps a bit too on the nose for my taste, but one appreciates what she’s doing here. Because for her, and so many others — for most people I think — there isn’t any so-called “authentic” single identity to return to at all. We read widely, and wildly, and the thing that marks out a good from a bad reader isn’t how much she knows but how sensitive she is to the project of what the other is doing — which she might then find interesting and take up, or sweep aside.

Capildeo’s shifts in tense between past, present and future destabilize the notion of what was, is and will be, and her activity itself suggests that all classics might be rewritten this way, with other voices such as those of women (for Capildeo, who self-defines as “they” and writes that she “self-presents” as a woman, an ample concept), on the sidetracks and rusty roads untaken left behind by the history of victors, where the trace remains:

There are too many women in this play,

all of an age to bleed; none bore children.

Lunar and silent, they have spread a field

of blood beneath the action. Dirt has skirts,

smooth roads rust, tiled surfaces tainted

with vinegar; nothing wipes nothing out,

nothing can be reached directly; nothing

that does not shed a lining, shudder, rubbish

the chance to make one clean sweet queen bee line.

Behind this bringing together of different registers, ideas and voices, there is an idea exploring such areas of shadow and rust, of going back to unexplored veins of history to discover the violence there but also the untapped joy, instead of resigning ourselves to the grey bureaucratic everyday to which we find ourselves confined.

To imagine other stories in history, and not just those linked to one’s own identity, is a form of resistance and holds liberating potential. After all, the “identity” we currently hold and the words we use are linked to such historical, colonial violence, which affected language. Everything is contingent, all is a counterhistory. What other parallel universes might exist? Capildeo helps us to explore them. As one of her personas writes: “When the British and the Spanish and the French and the Dutch and the Yankees and the Portuguese took away your language, I grew strong eating your tongues.” Such violence behind history comes through in Capildeo’s style, too, with its phrases that smash into each other, refuse a “clean” read, and leave a measure of incomprehension, but are also sown with possibility, “seeded with unfoldings”.

All of this might sound heavy, but it isn’t — thanks in large part to the light tone, the playful formats, and the ambiguity of the speaker herself. One of Capildeo’s preferred characters is the Fool, the one who makes language jokes like “gecko in a wall-zone” the one who through performative clowning can say what others do not, the one who speaks the truth. Thus Capildeo, with ludic skill, erases many givens, erasures necessary to create something new: “put a line through: meaning (…) put a line through: my”. But what’s left after we get rid of the drive toward sense, the established versions of history, the autobiographical first-person? Temporarily we might get closer to tree and plant life: “You’re indecipherable like a tree, and treelike you proliferate your gestures.” I don’t think it’s a mistake that so much writing these days is coming back to ideas of nature, as a source of poetry, as consolation, as another track through the foliage of events: “Nightly she sings on yon pomegranate tree.” Capildeo goes farther with her non-anthropomorphism, becoming not just objects but determinants from biology, sociology, physics:

I was the hurt that hobble the angel foot. I was the rot that spread in the forest’s root. (…) I am the nerves that push the mad president’s hand to push the button. I am the last words that you forget to utter. (…) I am the child bride hymen beneath the fingernails of the lawyer, I am the coat hanger in the cupboard of the priest wife room, I am the terrorist vampire from the Lapeyrouse tomb (…) I am the biological vector that turns the suicidal farmer’s harvest to ash. I am the force that shatters the astronomer of freedom’s telescope to splinter in his eye, I am the widespread lack of education that blind your comrade and make him cry.

These lines come from my favourite piece in the book, “Midnight Robber Monologue”, taken from a supposed play in which “Robbers duel in Tamarind Square, challenging each other with their sweeping actions and speeches that beat back the aeroplane Concorde breaking the sound barrier”. The force of this voice is a whirlwind, otherworldly. “The Robber is older than you can ever understand. He seizes the present. He is Fear itself. He is the eternal shadow underpinning all the five continents’ shifty land.” Time itself is undone:

At the age of minus six hundred and sixty six, I met the seraphim and cut off their pricks. At the age of minus seven, I cast down heaven into the Labasse. At the age of zero I forged my own cutlass. At the age of five I took your life, and your life, and your life. Your lives were sweet, and zombification was complete. At the age of nine, darkness was all mine. From the age of ten I operate as a ageless robber douen.

Faced with such “other” forces, we confront an impossibility of contact. This failure of communication, the silences made by others without our consent, and those we ourselves make for which we are responsible, is another theme. There are always things unknown even between the poet and the reader: “there is always, / even between the lines that speak / of breaks & brakes, / always someone else / who was present in writing – / when you thought you / knew – who you thought you were reading – / no means – in the garden singing”. The silent body outside of the text is a constant in all the mysteries: love, violence, writing. Capildeo notes the connection: “Love’s an enigma like murder.” Her most love-filled poem, “Reading for Compass: Response to Zaffar Kunial, Us”, is filled with a sense of the sacred and the aura of an appointment somewhere beyond, a rendezvous in some mirage of night with a fellow poet:

This isn’t what I’m used to. I grew up

as an inventor of voices for dead

books, impossible, inherited, odd

volumes, middle slices missing, made up;

colonial texts for memorisation

autoexecuted in rolling tones;

‘Indo-European’ languages drunk

like milk alchemised from blood, acquired

history. I know in my bones a desert,

or somesuch suddenly green lush place, where

our ancestors could have met with opposed

weaponry. What has survived of this is

us. And your advice: take heed of the vowels.

Repeatedly, in her work, as here, Capildeo defines and challenges what poetry is or does. “Every poem an ouroboros,” she says at one point. At another: “Reading this returns me to my body.” Elsewhere: “Who said which language / the book had to be in, anyway? / Fuck that shit. Now that’s a poem.” We are some ways beyond (or lateral to) Larkin’s “This Be the Verse”. The section of the book with Capildeo’s versions of Muriel Spark, an exploration of Scottishness, further complicate what poetry is through the incorporation of folk songs, wolf tales, and other popular materials.

The heart of the book, in my view, is a section that initially seems a jarringly non-fictional, near scholarly exploration of the life of Guyanese writer Martin Carter (1927-1997). In the context of the book as a whole, it makes sense. Capildeo’s interest in Carter has to do with her interest in performance, and with relivings (not responses or reworkings, she emphasizes). Out of the work of Carter, with “his naturally enigmatic and quasi-modernist intellectual approach to innovation”, she has created new “syntax poems” to be performed by several voices and bodies. For several pages she describes the elaborate performance on the basis of her poems made from Carter’s, “a living, not anatomised, version of practical criticism and close reading” with the goal that the audience will have “participated in a sense of call and response, cry and chorus, intimate camaraderie”. Carter’s original poem “I Am No Soldier” is rousing and soul-stirring: “O come astronomer of freedom / Come comrade stargazer / Look at the sky told you I had seen / The glittering seeds that germinate in darkness”, and Capildeo’s version turns this into a bewildering yet sensuous experience. Martin Carter is a “comrade stargazer”, and all of us are brothers and sisters on this earth together, linking arms and looking toward the heavens.

While the original poem is more or less comprehensible, the vertigo-inducing new form necessitates a return to the page, to elucidate the concept behind the work. These pages in writing, Capildeo says, are both “a record of the ephemeral”, and an instruction kit: “These materials are primarily an encouragement to readers to prepare their own kinetic, immersive, or collaborative responses (should they so wish) to any text of their choice.” The seating instructions for a colonial classroom, chart and student exercises at the end are partly serious, partly a devilish wink at the poetry apparatus that provides exercises meant for students to “understand” poems.

I do wonder about the relationship of this kind of poetry to academia, since it seems to require a restitching after the unpicking. (Capildeo wrote this when she held the Judith E. Wilson Poetry Fellowship from 2014 to 2016, at the University of Cambridge.) An interesting sort of academia might perhaps forge an atmosphere beyond the accelerated news-cycle-driven world to explore some of the avenues of difficult poetry, which Capildeo lays out.

A new criticism would involve not just the page, but the body, and would explore the connection between units of sense and their connection to physical movement: “What is the smallest unit of sense that arises from the joining-up made by the eye-movement (or that catches the inner ear as the eye moves)?” Capildeo, in her notes, pays close attention to breathing, rhythms, invocations, and repetitions, and treasures a constant movement, with a lack of interest in settling. The performance itself ends with a dance: “we had to anchor ourselves in the text and live out its twists and turns, in order to make sure we did not get physically stuck at any random or significant point in the set-that-was-not-a-set.”

The last few poems felt a little miscellaneous, or at least I’d have put them before the climax of the Martin Carter poem. But I appreciated their inclusion, especially “Poems for the Douma 4”, about four people abducted from the Violations Documentation Centre, in Syria: “Nuance has more off switches than lovers. Men stormed. Men do not storm. These are not natural phenomena. Sometimes I hate my trained mind.” Such interrogations of language, which gut it, draw out its viscera, sew it up into new beasts, then dance the unidentifiable forms into life, make any reified notion of identity seem unbearably tedious. There is so much more we can do.

About Jessica Sequeira

Jessica Sequeira is a writer and translator from California, currently living in Santiago de Chile.