You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Telling people about the musical I’ve just seen at the Young Vic is amusing. “What’s it about?”, they ask, with that amiable expression used when discussing musicals – a sort of a feel-good, happy subject of conversation, as unchallenging as the weather or a weekend in Bruges.

“Oh, it’s about nine men who were wrongly accused of raping two women. Back in the thirties, in the USA.”

It’s a little like introducing a disastrous tsunami into a conversation about London rain.

This is why the show works so well. It tells the true story of the Scottsboro Boys, nine young African-American men arrested for a crime they didn’t commit. In March 1931, these teenagers, aged from twelve to nineteen, were falsely accused of raping two white women on a freight train to Memphis.

The young men narrowly escaped being lynched and the case went to court. Assigned incompetent lawyers, they were condemned to death despite a lack of evidence. The case was taken up by the Communist Party, who organised a proper defense team for the accused. A series of appeals and court cases followed. However, the obvious innocence of the boys and the admission of one of the women that she had lied about being raped were insufficient to convince Southern courts. Juries kept delivering guilty verdicts and the death sentences were changed to lengthy prison terms. The case dragged on for years, divided the nation and became the symbol of the Deep South’s racist attitudes.

The court cases and the young men’s prison ordeal form the dramatic conflicts of this musical. As spectators of a musical, we are programmed to expect that these plot complications will be resolved and all will end well. We root for the heroes; we keep hoping, but the genius of this show is that deep down, our hope is tinged with despair. We know that this is a real story and that there is little chance of a happy ending.

Throughout the show the carnival atmosphere lulls us into a comfortable enjoyment; at the same time, the excruciating unfairness of what is happening to these characters grabs us by the throat.

These feelings of merriment and shock coexist in most of the scenes. For example, a disturbing dream sequence involves a tap dance in a prison where an electric chair sizzles and sparks whenever a human body comes into contact with it. Horror threatens but the audience ends up laughing.

The music and lyrics were created by Kander and Ebb, known for their hits Chicago and Cabaret, with a book by David Thompson. Directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman, The Scottsboro Boys opened in New York in 2010 and toured America, receiving rave reviews everywhere it went.

The show uses the controversial minstrel format, which leads to sophisticated reactions from the audience. We are able to balance the unease caused by the minstrelsy with our enjoyment of spectacular dance routines, our anger engaged all the while by the injustice of the boys’ situation.

At all times the form of how the story is told takes on a life of its own and appears to work in opposition to the subject matter. The conventions of the musical make us wonder whether this case is maybe too tragic – perhaps it is altogether too much to be relayed in this way. But its power is that it drags the distasteful piece of history into the spotlight, reclaiming it from the remit of more “serious” artforms. In the same way, the minstrel format makes it a complex play-within-a-play in which the performers tell us about the Scottsboro boys and through recounting the story, evolve and finally rebel against the master of ceremonies (Julian Glover).

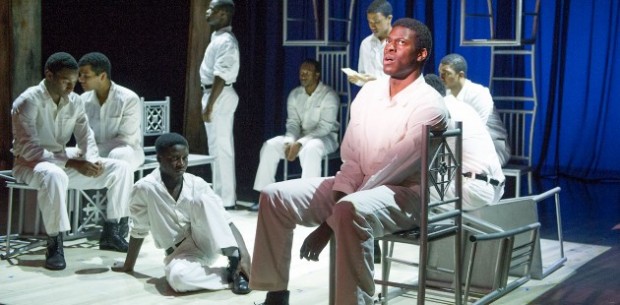

The stage is kept minimal and the cast use chairs as props to suggest anything from a cramped prison to a noisy courtroom. The focus is on the acting, the beautiful songs and the vibrant dance routines. It makes for a highly polished musical in which each performance is perfect.

The cast is a mix of American and English actors, with Londoner Adebayo Bolaji in the role of Clarence Norris. The same actors play different parts – for instance two male actors, Christian Dante-White and James T. Lane, also act the parts of the women convincingly. They are hilarious in drag while relaying Victoria Price’s deviousness and Ruby Bates’s bewildered fear with great precision.

The Scottsboro Boys gives an unsentimental account of a tragic event that destroyed nine lives. It is also a reminder of an important period in history – the case influenced the burgeoning US civil rights movement. It is only in April this year that the Scottsboro nine were posthumously pardoned by the state of Alabama. On a video on the Young Vic website, Dante-White expresses the hope that the musical will encourage audiences to think about the events and look for information about them. The Scottsboro Boys manages this successfully, as well as – or, rather, because of – providing breath-taking entertainment.

The Scottsboro Boys is on at the Young Vic until December 21. See the theatre website for more information.

About Patricia Duffaud

Patricia Duffaud is a writer of mixed French and Northern Irish origin. She writes short stories, features and reviews and her work has appeared in Wasafiri Magazine, the Puffin Review and Thresholds. One of her stories was highly commended in the Gladstone's library's Mystery Lady short story competition. She is currently non-fiction editor for Litro online.

One comment