You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Cindy Withjack: Hi! How is your day?

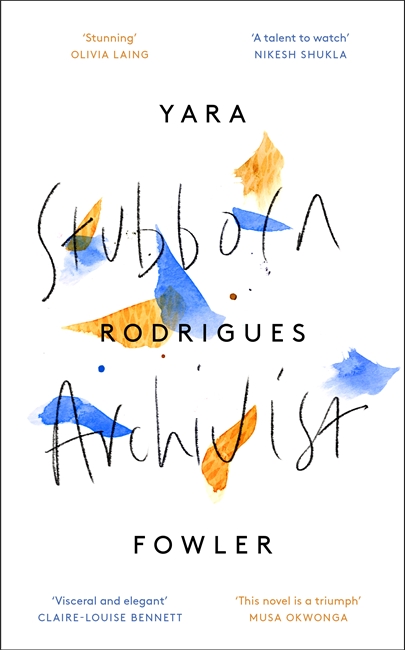

Yara Rodrigues Fowler: Yeah, good. Having a book out is weird, though. I get a lot of people from school, from like ten years ago, messaging: “Hi, I read your book; I have feelings.”

CW: Does it feel surreal?

YRF: It feels both surreal and good, but also like, “Wow. This takes years, and I’m really ready for it to be out in the world.”

CW: How long did you work on Stubborn Archivist?

YRF: I wrote a first draft that was much shorter. I finished that in 2016. [My agent] took it out to publishers, and they loved the voice but wanted it to be a normal book length.

CW: Was it previously more like a novella?

YRF: Yeah, because I was thinking about The House on Mango Street. I don’t know how many words that is, but it must be quite short. [Publishers] didn’t really want something that short.

CW: You ended up with an absolutely gorgeous novel. My immediate thought when reading the first few pages was how great it was that you were write candidly about a woman who experiences real, explicit bodily functions and troubles. You write about her Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and how it is potentially anxiety-related or trauma-related. Did you feel like it was a statement to write about a woman shitting?

YRF: It really did feel natural, but it also felt like a big statement. I think it felt natural because it’s part of everyday life, why shouldn’t it be in a novel? When you’re reading a realist novel and it leaves out things that are part of a person’s everyday experience it reminds you that while realism pretends to be super true-to-life – it’s not; of course, it’s super constructed. Things – like bowel movements – are left in or out depending on whether they are deemed appropriate or worthy of literary representation. I wanted to disrupt that convention, show some of those things. For this character, like you said, it’s not totally clear but the IBS seems to be anxiety-related and tied up with her mental health and also her relationship, maybe, to trauma and sex. She often feels quite alienated from her body, from her femininity. IBS is really common, and it’s not something that has come up in Stubborn Archivist reviews or interviews, so I’m really glad you’re bringing it up.

CW: It’s annoying that I was so ecstatic to see that you had written about something so natural. It actually made me think of Charlotte Roche’s Wetlands. It’s a contentious novel because of how Roche writes about sexuality and the body. In general, readers seem to find it off-putting or disgusting because the novel is hyper-focused on a female character who has a serious anal injury. And, like with your novel, I wonder if the reaction would be so extreme if the character had been a man. Usually bodily functions for men are written to be fairly comedic – puberty or masturbation – while for female characters it’s seen as scandalous or gross.

YRF: The thing that I think is cool about including it is that it isn’t just a way of talking about trauma that is very survivor focused but also, it’s a way of talking about the gendered body and the kind of alienation that you might feel from the kind of gender performance and sexuality that the world expects of you – especially with this character who is hyper-sexualized. I wanted to write about a gendered body and a female body that wasn’t just woman equals ovaries and vagina, which can be essentialist and has been very overdone.

CW: I’ve marked up the portion of Stubborn Archivist where the protagonist is struggling with her inner dialogue – I think it’s possibly my favourite section of the novel. She’s trying to convince herself of something by saying, “There were good times. Come on. Be honest with yourself.” There’s a clear perspective change throughout that section. Is she having a conversation with herself or with someone else?

YRF: I think that is one of the more complex parts of the novel. Certainly, it can be read as a dialogue with herself, but it’s also a dialogue with the text, or whoever is in charge of the text: her, the writer, the reader. She could also be talking to different versions of herself in time. At that point in the novel, she is attempting to move into a place where she can name what happened to her because [the sexual abuse that occurred] was part of an intimate relationship.

CW: That makes me think of the tense scene during which the protagonist confronts her ex-partner. You did such a great job of making his character a layered person because people are rarely just one thing or one way. Did you have the inclination to make him a bad guy or did you always see him as more complicated than that?

YRF: At the start of Stubborn Archivist, what we get of his character is filtered through her memory or her looking through his Facebook page. I wanted to capture how it is now – it can feel like you’re involved in someone’s life just by looking through their social media. Partly because, maybe, they haunt you for some reason, but also because we can just look at people whenever. It’s this feeling of sharing space in a very immediate way. In the scene you’re talking about, the experience is so different from how the reader was introduced to him. It’s almost as if there are two of this man because she shows who he is through her memory, then in that scene he’s there, live and speaking in the moment. But no he’s not a monster – rapists generally aren’t, they’re more likely to be our brothers, uncles, partners etc. If anything he is more of a blank. A site of terror and banality.

CW: It feels like something she is doing very much for herself, in that scene, by confronting him. Even though his reaction is so base, it’s clear to the reader that she hasn’t arranged this meeting to illicit a reaction from him. Because you didn’t villainize him, it highlights how confusing the situation really is for her – this wasn’t a stranger, this was someone she shared her life with, with whom she had a long-term, loving relationship.

YRF: It was really important for me to make him a really average guy; he plays football with his mates, he’s probably quite conventionally attractive, he’s on his way to becoming a doctor. It’s likely there will never be any sense of justice [for what he did] in any sense of the word. I wanted to show the abuse that can so often happen within a loving relationship, and we often don’t have the words for it when it happens.

CW: When you were drafting Stubborn Archivist, did you ever plan to include any scenes depicting the abuse?

YRF: Before I started writing, I thought a lot about how trauma lives in different texts and the ethics of that. I thought about it less actually from a psychological framework and more from a literary framework. I studied Junot Díaz and Edwidge Danticat – thinking specifically about the way they write about dictatorship in the Caribbean and Latin America. For example, if you create a war documentary and all you’ve included is pain and roll credits then, assuming the audience don’t directly share that specific experience, all you’ve really done is say, “Look how awful this is.” What that framework doesn’t explain is how the pain came to happen nor does it explore how the reader is complicit in that experience. In Edwidge Danticat’s book The Dew Breaker there are several chapters that are linked together by the behaviour of a torturer, and what it does is show the sprawling, spidery aftereffects of what happened [to the victims]. When I was writing Stubborn Archivist, I wanted to focus specifically on the impact abuse has on survivors and ask where that comes from – not letting the reader off without a sense of complicity. It’s not a “Me Too” text, in the sense of how the movement became popularized (rather than what Tarana Burke created). Stubborn Archivist is not a novel that ever tries to convince you of something. That was important because I didn’t want it to be a novel for people who needed to be convinced of something. I wanted it to be a novel for survivors. I take issue with this idea of offering “proof.” I think that’s part of the stubbornness of the text – the withholding that it provides.

CW: That’s so beautiful.

YRF: Thank you.

CW: Was the confrontation scene ever longer? I imagine the conversation didn’t exactly end there with his reaction, “I loved you so much.”

YRF: It’s really like, she said these things to him and what kind of a response is, “I loved you so much.” It’s also about the fact that the way people love can be violent, and often in that situation the person being violent will claim that their violent behaviour is actually loving or that because you love each other something is owed. I wanted him to say something that could potentially make a reader feel sympathetic toward him, then question, “Wait. Do I really sympathize with this guy?” It sort of takes us back to the fact he’s not a “monster”. I originally wrote that scene as a standalone piece with the man in second person, and the challenge was almost like getting the reader to see him humanized and sympathetic, thinking that maybe what had happened was actually OK until the end of the conversation. Eventually, that didn’t feel appropriate to me in the context of the novel to make him you. I wanted the reader to really feel a potential ambivalence in her, that pull she feels for this person she loved who also abused her. And that’s quite ugly, isn’t it? A shameful, confusing feeling.

CW: Is this male character the same character who talks about Brazilian pornography? Is that significant to his abuse?

YRF: Yes, I think we assume that. Interestingly, there was one review that brings up how he asks the protagonist to speak Portuguese in bed – but she offers to do that on her own. So, [as readers] we don’t really know how much the pornography and [exoticism] plays into things. From the male characters’ point of view, pornography is a large part of how young men understand sex and certainly how sex works and how to treat a woman during sex. There are so many kinds of racialized pornography and illusions around how different types of women should be sexual or what their preferences are based on that racialization. But it’s more complex than his character watching a degrading porn video and now he’s going to be abusive. I wanted to document the complexity of her idea of her own sexuality – what she believes, at a young age, to be sexy and powerful.

CW: That is so evident in the chapters where the protagonist is a child and strangers often comment on how beautiful she is, and how pretty her eyes are, and so on. I think it’s very powerful that you didn’t start with that – you showed her as a sexualized adult and backtracked to how that sexualisation isn’t something new to her.

YRF: There’s an environment of hyper-sexualisation that she feels ambivalent towards when she’s young. Eventually it’s about that moment of recognition, especially when you’re young, that the world finds you “sexy.” Originally that can make someone feel quite powerful – the novel shows her getting dressed up and being able to get into clubs. That’s why I reference Lydia Bennet [from Pride and Prejudice]. It’s a sexuality that is projected onto my protagonist; it’s not something that she’s chosen, and it takes quite a while for her to define sexuality on her own terms.

CW: There is an air of coming into her own and feeling empowered by the end of the novel. There’s a focus on her own connection to her body and the langue of that last section, “Leaving (Coming)”, feels quite positive and powerful. Is that because she confronted her abuser and has physically returned to a place that is culturally significant to her identity?

YRF: It’s definitely both. The confrontation is important and shortly after that scene she is on an airplane going to Brazil. I wanted the third and last section of the novel to face forward. I’m very wary of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak calls the “nostalgia for lost origins.” It’s not like if the protagonist moves to Brazil she will suddenly find inner peace. What I wanted to do by using the present tense in that last chapter – especially because there is a lot of relevant political tension, the world around her is falling apart – is show the joy and presence she now feels within her own body. In that last scene she’s dancing, which is a very “in your body” thing to do, and there’s a character with her, Gabi, who asks, “Do English people have to be drunk to dance?” And it’s sort of like, maybe? Maybe she is an English person? And maybe she does have to be a bit drunk to dance in Brazil? But she’s still there, dancing, in her own body, and that’s OK. She doesn’t verbalize the movements of her body – the line is, “Her body moves.” It’s such a contrast to the start of the novel and the “broken body” and the bodily alienation that she felt. There’s also a very quiet, perhaps queerness in that dancing scene, as well. And all of that combined isn’t exactly a forever resolution, it’s a joy. It’s not that we have to see her in a new relationship or living happily ever after. It’s very much that she arrived at a place where joy is possible. I thought a lot about what I wanted to offer my readers in terms of Stubborn Archivist being a survivor-centred text. It was important to me to offer some joy.

CW: There’s a visual passing narrative throughout the novel because she is blue-eyed and light-skinned, but there’s another element of passing because her trauma goes unseen. She has that experience when a stranger says to her, “You don’t look like you’re from here,” and she responds, “Well, I am from here.”

YRF: That’s such an interesting way of looking at it – passing in those two different ways. She doesn’t reveal much to her parents. We know that by the end of the novel she’s spoken with her friends about what happened. At the start of the novel it’s clear that she feels very much alone, remarkably alone. A lot of the novel is about balancing that isolation, and in a lot of ways she’s frustratingly private person. Part of the passing narrative that I think is important is the way she’s seen around her Brazilian family, which is really European and white. I wanted to flag that in Latin America there are white people, there’s a white ruling class, and there’s white supremacy. It doesn’t make sense to talk about Brazil without including that. I wanted to show the everyday ways that whiteness is elevated and thought of as beautiful – the constant comments about the protagonist’s eyes and her small nose.

CW: Writing a novel is deep labour, mentally and otherwise. How was it writing this particular character who is so intense and guarded?

YRF: I wrote a much shorter version that focused more on silence. It was really hard to flesh because that’s such a significant aspect of the text: not everything is translatable, things are withheld. I was working fulltime while I wrote Stubborn Archivist. It was lonely. It was quite a lot mentally. I’ve been very privileged but it’s always hard writing a novel under capitalism I think. [Laughs.]

CW: [Laughs.]

YRF: In terms of actually writing the novel, I thought so much about the ethics of writing this particular story, from a really theoretical perspective as well. There’s so much about translation theory that went into Stubborn Archivist – not so much the theory of translating literature, but thinking about what it means to live in translation – how migrants live and the politics of explaining, conforming, assimilating into a majority language or culture. So while I was concerned with the story, I was much more concerned with form and the possibility of writing with silence and gaps, and of course untranslated Portuguese. I wanted to create a novel that had oral texture and lots of women talking. Something I did was record myself reading a section or a chapter out loud.

CW: It’s such a conversational novel, so it makes sense that you worked on it in that way.

YRF: That’s also how I worked on the novel while commuting – I could listen to it and decide what sounded right.

CW: Are you reading anything right now or listening to any audio books? You know, for fun?

YRF: Oh my god, can you imagine?

CW: [Laughs.]

YRF: Reading books is such a privilege. It’s fun that publishers are sending me free books. Whenever I do events with authors, I make sure to read their books. Reading feels like work these days, and I suppose it is. I’m currently reading for my second book – very serious texts about politics and race and Brazil. I was recently sent a novel called The Sun on My Head by Geovani Martins who is a Brazilian author. It’s coming out in the UK later this year. It’s a collection of “contos”, which is like short stories. It focuses on a world comprised of the same people, but it’s not a novel. The English-language translation is interesting, though it does leave in a few Portuguese words. The Sun on My Head is a really powerful book. I’m also rereading Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. Sometimes it’s nice to read something familiar.

CW: I imagine it’s all still quite overwhelming. There’s a comfort in rereading novels.

YRF: Definitely. When I wrote Stubborn Archivist I wanted to bookmark this period of time, 1991–2015, which has been a time of relative political peace – in Brazil and globally, as well as in the Amado family, because of the end of the Cold War. Or it felt peaceful at the time at least. Although I was aware of the rise of the right wing in Brazil, I had no idea when I was writing that there would be a coup or that someone like Bolsonaro would be elected. The themes in Stubborn Archivist, that underlie the story I’m telling about an upper-class Brazilian family and its relationship to Europe – white supremacy, patriarchy, colonial violence in brazil and the dictatorship – feel more urgent than before. (And perhaps it was naive not to have felt that urgency before.) It feels more urgent to me as a writer to tell stories that remember the foundational violence that Brazil was built on – slavery, the genocide of indigenous people, how sexual violence was weaponised, how white supremacy was intellectualised – and how they’ve taken us to where we are now. Both in Brazil and in the UK. I feel my task is somehow to create writing that remembers these things – a place for slow thinking and remembering – but that also brings of joy and helps the reader imagine a better way for things to be.

CW: Stubborn Archivist is such a force. Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me.

YRF: It’s such an honour and a privilege to have readers like you who ask such fantastic questions. It really is a joy.

Stubborn Archivist is out now from Little, Brown.

About Cindy Withjack

Cindy Withjack holds a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of Birmingham and is a PhD candidate at Lancaster University, where she is writing a novel. Her work has been published in theBurg, From the Fallout Shelter, The Huffington Post, The Journal, Slice Magazine, Litro Magazine, Women are Boring, and Banshee.