You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingRead part one of “Lulim Lalai: The Power of Life In Country” here … and part two here.

Visiting the caves

When the time is right to visit a sacred cave near Wjingarra Butt Butt, Isobel’s sons Neil and Bart bring a rake. They might sometimes resist chores around the camp, like washing the dishes, but they don’t need to be asked to do this job. They will sweep the ground inside the cave to keep it looking tidy, and also so that when Isobel returns she will be able to date the fresh tracks. She’s creating a time stamp, the way they did in the old days.

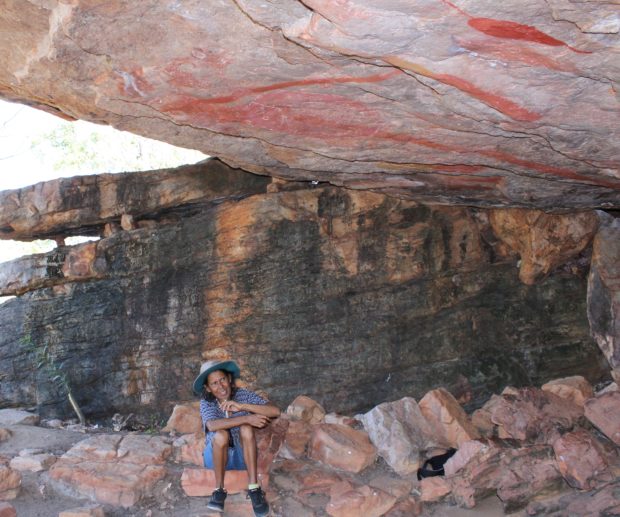

Two rocks naturally form a chair with a back, inside. “I like to think my grandmother sat here like this,” Isobel smiles, as she takes up the position. “It’s perfect for her, see.”

Images applied across rounded, under-hanging rocks, run almost the length of the narrow cave; the impact of these shifting perspectives is mesmerising.

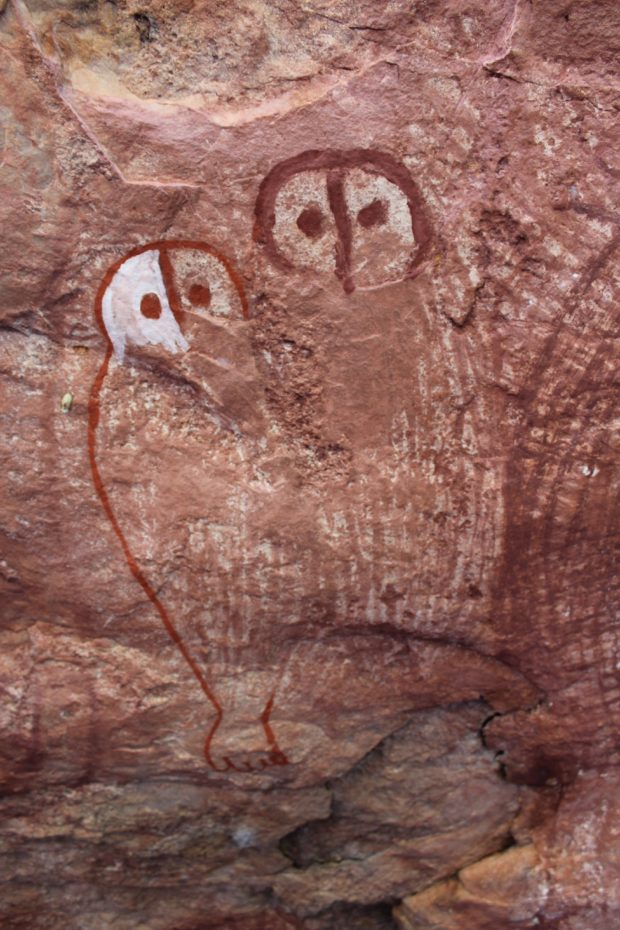

There’s a calf whale and it’s mother, a turtle and a Wanjina, Isobel’s totem a huge stingray, fish, dugong and owls.

She explains that the munnumburra, the elders, treated cave visits ritualistically sometimes. You might only visit during a correct moon. You might camp for three days first, before it was time to go into the cave.

When the time was right, you laid on the ground, looking up at the paintings across the cave, and allowed yourself to dream, connecting to the gods and stories.

The remarkable Numbree or Raft Point is arrived at by boat, its red cliffs rising more impressively than the scale of any cathedral. It’s impossible not to be awestruck.

Here we landed the boat to meet tourists from a passing cruise ship. Isobel’s daughter Naomi greets the visitors, daubing red ochre on each cheek. This signifies to the spirits that the tourists are welcome guests.

We walk them up into the hill, overlooking the sea, to a sacred cave, where son Neil and Isobel explain the paintings.

Neil encourages visitors to lie on their back, looking up at the images, letting the mind wander as the art plays across the rocks above.

Breathtaking images here include the Gwion, incorrectly called Bradshaw paintings in the past, after the explorer Joseph Bradshaw. For many years white people offensively said Gwion images belonged to an “earlier mystery race”, but this has been systematically debunked by western science as well as by the tribal elders.

The Gwion is joined in Numbree by a half-moon Wanjina, watching over a fishing expedition. This cave tells many stories. It’s a fish, or jaiya Dreaming connected to the creation deeds of the Wanjinas, when they made the land and nature within it.

Neil and Isobel explain that a great flood wiped out most of the people, along with the wurnan – the social legal system – and Wanjinas returned to earth to re-set wurnan. This wurnan included the contract that only appropriate men would retouch the sacred cave images.

Some images were retouched by appropriate tribal members just five years ago. An earlier touching up of these images was recorded by filmmakers in the ’70s.

Some images haven’t been refreshed and look faded. It’s agreed that the original cave paintings here are Paleolithic, predating Lascaux in France or Altamira in Spain. It is explained to tourists who visit here, that this very area has been dated as having continuous occupation for at least 50,000 years.

The relationship between the art Isobel is responsible for, and the outside world, is a complicated one.

Arguments over ownership of the paintings bogged down her elders while they defended their heritage for decades. While they were thus occupied, the vulnerability of Isobel’s tribal culture was exploited.

When Isobel was a child, an elder, George Jomeri, made a print of her hand on bark, as part of a scene shot by filmmaker Michael Edols for Floating … Like Wind Blow ’Em About (1975).

Uncannily, when Isobel felt a stirring to find this work, in 2015, her partner discovered that Sotheby’s in London had just sold it at auction for £13,750. The provenance suggested it had been legitimately procured from the community.

“Nobody had my permission to take this or sell it,” Isobel says. “Or the permission of my uncle [George Jomeri] at the time. There’s a lot of this that goes on.

“It’s hard because people come back and say we had permission, and when we press them, they say someone told them at a liquor store or something, which means they gave our people grog to get things.”

This is part of the tragedy of the history that Isobel is working to overcome, to reclaim what is theirs from the savage days of “floating in the wind”.

Sacred Worrora objects from junba, corroborees and rituals, have found their way into museums, “But now they are not used for ceremonies, they have lost their magic. They are just bits of wood to us,” Isobel says. “We don’t understand why anyone would want them outside our country or for no purpose.”

For those who have broken the Wanjina laws, there is a deep regret and sadness at the inevitable consequences suffered; unexplained deaths and serious accidents.

Clues left by family

Near the entrance to one cave, Isobel points out a gap in a tree trunk, where layers of bark have been removed. “You see here, that’s been used as a baby cradle,” she explains. “We call it angham. You can see where someone pulled it out.”

Clues such as this, left by old clan members, are found throughout the estate. Another time, walking along a rocky river bed near Wijingarra Butt Butt that fills during the Wet season, we come across a certain rock fig tree that Isobel can see has had a beehive, full of honey, removed, and a soap tree that ants have built their nests around.

Our walks involve stopping to decide what the bird and animal tracks are telling us, discussing what animals the excrement we find might be from, observing birds and animals.

“But we were lazy gardeners,” Isobel laughs. “We just burnt the land, that’s so much easier.”

Before moving on from a camp, Isobel’s nomadic family performed controlled burning, to dispose of waste and regenerate the landscape. Now, each year, when the family leaves Wijingarra Butt Butt, the state fire authority does controlled burning around the site with the help of tribal rangers from Isobel’s community, who have done ranger training.

This creates a firebreak around the site ahead of the tinderbox heat, which soars toward the end of each year, just before the weather breaks in the Wet season.

In 2006 the elders made an agreement regarding an iron-ore mine on Koolan Island. It’s outside Lulim but on Worrora tribal land. According to the deed of trust, royalties are shared among all the descendants of the native title claim.

This money has lifted the Worrora people, giving the tribe its own money, paying for school and university fees, for example, without the need to jump through bureaucratic hoops for a government-funded education.

This, along with some grant money from the government, was used to build the camp infrastructure at Wijingarra Butt Butt which Isobel and her children now occupy. The camp and the setup are still a long way from what Isobel needs to effectively manage the country, and the steady influx of tourists with a thirst to visit the land and get a glimpse of her culture.

Isobel is candid about some of the more recent history, including taking the local lands council to the Human Rights Commission for discriminating against her as a female, a move which led to a major straightening out of her position, and the steady healing with her tribal administrative structure, to be where she is today.

“Things have really changed,” she says. “Being able to live here makes a big difference. It wasn’t something that was easy to do when I was growing up, so far away, having to be in Derby.”

Even further away, two and half hours’ flight south, Perth is where Isobel was sent to school, aged fourteen. Her mother told her, “You have to go learn your almara ways now.”

“It was really important to my mum that I was educated, that I learned English, and got away from Derby. And it did make a big difference,” Isobel says. “At first it was really frightening. Lots of things were different. I’d never eaten vegetables like peas and corn – the sorts of things I found on my plate.”

She moved back to Perth with her six children in the late 1990s with the help of her elders and the late author Hannah Rachel Bell, who was a confidant, friend and para-legal of the late famous Ngarinyin elder David Mowaljarlai.

“I’ve done the same thing with my children,” Isobel says. “They are great at sports, but I wanted them to be reading, writing and counting. We are clever people; we respect education, even though it’s difficult to leave our place and be in the city.”

Writing Worrora

Writing the Worrora language is a fluid business; there’s no accepted spelling just yet. The reason is obvious as soon as I try to write down the family’s tribal names, with Isobel correcting me where need be.

Isobel is Wudugu. Older son Neil is Winjaryin, but he’s named after his father, whose name Isobel doesn’t say now that he is dead. So she calls him Junior, always. Daughter Naomi is Moloddginy, named after a dead grandmother. And younger son Bart is Murungnu.

Spelling is always a frustration, and something regularly prone to revision by academics.

“It gives me a headache to look at the letters and try to match them up with the sounds I’m making when I speak,” Isobel says. And I agree. It’s like trying to translate bird song into writing.

The boys take their father’s last name, Maru, and the girls take their mother’s, the adopted foreign name Peters, given to her family by missionaries – it’s from the Christian name they gave to a grandfather.

Love and duty

And there’s another in their family, the white man from Perth, Peter Collins. As a reporter for The West Australian in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Peter began working with Kimberley tribes on tracking stolen sacred artefacts.

In 1994 he progressed to working with Isobel’s elders, including Paddy Neowarra, on reclaiming their history. At the time, well-funded archaeology circles denied that the tribes could claim cultural continuity over tens of thousands of years.

His was almost a lone voice at this time in presenting the Aboriginal view. But things have moved on significantly since then and those ’80s and ’90s ideas are now accepted as having been racist and plain wrong – possibly motivated by a desire to exploit the land.

This explains my connection as well, as a long-time friend of Peter, a Perth-based fellow reporter on the newspaper at that time.

When the elders grew to know Peter, they explained that they were concerned about the next generation, who weren’t listening to the law and knowledge that needed to be passed down, who weren’t spending time in country. They inculcated Peter with their vision for the community and passed to him. He describes it as “just a little, but enough” knowledge needed to “do his little bit” to help achieve that.

Peter and Isobel both describe their coming together as like an arranged marriage, but are careful to qualify that it wasn’t anything negative, like the forced marriages of foreign cultures.

“Our old people bought us together,” Isobel says. “I needed someone to help me with the children. I also had the children of other people, like tribal elder David Mowaljarlai, with me at that time.

“And I needed help with getting my land back under my control. Peter was the right one to help me do that, he had worked with my old people on their land and culture rights and knew the way we were meant to do these things.”

Despite the often misapplied-notion that women are second-class citizens in Aboriginal culture, in Worrora culture, while women traditionally live in their husband’s country, they never surrender their rights to their own country. Often, when required for law and culture management, the husband will live with his wife’s people, to help manage their estate.

She explains, laughing, “People have said we are like the Queen [Elizabeth II] mob that way, if we got no men on the line, the woman has to follow that line on.”

In the late ’90s, Isobel had a serious medical issue that led to her staying near Perth’s major hospitals. Here, she continued to project her children into the future her elders future her elders, like David Mowaljarlai and Paddy Neowarra, were arranging. And she provided a base for the elders as they moved up and down from the Kimberley.

Removing the community from the traps and destruction of alcohol and town life, and moving back to country, was essential.

Isobel’s place, often called Ngarinyin House, was an embassy in the city, where the tribe stopped in for a rest and a talk as they came and went on their cultural and often medical business.

Isobel and Peter’s “arranged marriage” in the middle of this wasn’t taken lightly by anyone, but was secured by the good fortune of their falling in love.

“It wasn’t easy at first,” she says, of meeting Peter. “I didn’t really understand him. But eventually I could see that he wanted to take care of me and the children; that he was a good man.”

And anyone who meets the pair will agree they make a wonderful double act. It’s a partnership dedicated to making the right decisions about Lulim and its sacred law. This is what’s hoped of tribal marriage, as well as enjoying each other’s company, which of course is what anyone hopes to get out of a relationship.

It’s not knowledge if it’s written down, you carry it

As the rocks change colour at dusk along the Wijingarra Butt Butt shore, they seem also to change shape. Huge tidal shifts alter the perspective too, shapes that weren’t there earlier appear, and vice versa.

When the sun sets, the skyline’s luminous tropical pink, mauve and orange surge and fade, making way for a final red glow before the darkness takes hold.

At night, tiny shells, of many different types, mobilise en masse around our feet, taken up by thousands of hermit crabs heading inland as the tide approaches. As they grow out of their shells, they abandon them for larger ones.

The resident quoll crashes about when we’re in bed, particularly keen on any biscuits that haven’t been secured tightly.

And the birds at dawn, in concert with the lapping waves, welcome the day in energetic and inspirational chorus.

Lalai, Dreamtime, also means the soft, unformed light of day, a metaphor for the new era Isobel faces, and the choices she must make for her country.

I want to record this important moment in time, scribbling notes discreetly and taking photos, but Isobel says, “You don’t need to write all this down, you’ll remember it. And if you don’t, we’ll remind you. That’s how knowledge works. It’s no good written down, you need to carry it with you.”

Men remember men’s law, women remember women’s law, and aunties, uncles and elders all remember the piece they’re responsible for, working together to look after the clan and the tribe with their shared knowledge.

In country, knowledge is no good unless it’s in your head – and your stomach. There’s no time to go and look it up. You need to know how to act in any moment, following tracks, looking out for the signals. It’s not just about avoiding dangerous fish, or sharks or crocodiles, or eating the right foods. It’s about traversing the right way through the spiritual elements of the land, so you can live well, and avoid getting hurt or going mad.

Isobel and her people believe they can pick up spirits from the land and this needs to be dealt with or bad things can happen.

For this reason, before I leave, of course I am, along with all my luggage, laptop, phones, cameras, everything, smoked well and truly. Isobel has packed guru stick, or cypress pine logs, in my luggage. Back in my flat, I smoke each room thoroughly, filling them with the heady, pungent smell of salt and pine oil.

What a woman

Isobel is by any standards a remarkable woman. She has raised her own six children, along with the children of others. For many years she did this as a single mother inside a community well documented as suffering extreme poverty and social violence.

She extricated her children from that without breaking their traditional ties to law, culture and community. She is a sole surviving female descendant of a tribal clan with scientifically documented presence in this area of the world for at least 50,000 years.

She has seven grandchildren. She’s the champion of humpback whales and other wildlife. And she continues the master plan of her elders, for survival in this time and place.

Afterword: The world’s oldest flood story

The Dreaming or Lalai story about the Dumbi, the masked owl … as told by Neil Maru Jnr (Winjaryin), Isobel’s son.

But the sons didn’t believe him and started sticking spinifex into him and plucking feathers out of the owl. Then they started throwing the owl into the air and saying, “if you are really the son the Wanjina then fly up into the sky”. And the third time they threw him up he flew to the Wanjina.

The Wanjinas were angry so they flooded the earth. Two children saw a hill kangaroo and they knew that it would take them to high ground where they would be safe from the flood. So they both grabbed on to the tail. And they are the two who started this generation or era of people.

If you would like to know more about what Isobel is doing in her country you can contact her at arraluli@gmail.com.

You can also check out her whale advocacy webpage https://arraluliwhaleproject.com.

Litro’s mission is to find the best and most exciting new voices in fiction and non-fiction from across the globe and give them a platform for their work. Litro wants to continue to showcase the best emerging artists. You can help us by supporting our Crowdfunder Today!

Subscribe to Litro Lab via itunes RSS | More

About Lise Colyer

Lise Colyer is a former news reporter who tells stories professionally now in her role as a PR director. She also writes fiction, mainly novels and poetry, and still keeps her journalistic hand in with news stories and non-fiction essays here and there.