You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The centenary of the October Revolution finds us in a strange place: nearly thirty years removed from the crumbling of the short Soviet century, with its neoliberal successor unravelling into the grotesquery and parochialism of nationalist populism. As museums and curators of communist memes try to “make 2017 1917 again,” we react with a conflicted mingling of vindication, nostalgia, and rue. The snide “told you so” retrospection of 100 years but also an envy of that bolshie optimism–ratios depending on your politics and tolerance for wall after wall of propaganda posters in Cyrillic. It’s hard not to be cowed by the scale and abandon of the Bolsheviks’ dreaming, especially from this age of budget ambitions, when all of our skyscrapers are owned by the Qataris, our infrastructure slathered in corporate branding and most grandest schemes to improve the world are apps and the sharing economy. At the Royal Academy these lost revolutionaries dream in gliders and Suprematist tableware. Across town in the Design Museum they’re fantasizing about a socialist transfiguration of the city—with horizontal skyscrapers, communal houses, “health factory” resorts, and a cosmically aligned “knowledge centre.”

Only one of the seven schemes featured in Imagine Moscow was ever constructed. Lenin’s mausoleum, the final sour note of the exhibit, is the exception. All others foundered on the realities of civil war, rapid industrialization, a dire housing shortage and frequently, gravity. An exhibition of six phantom buildings could be thin, and often Imagine Moscow requires you do just that, squinting at sketches and the occasional model. However, the exhibition meanders to its benefit. El Lissitzky’s Wolkenbügel (rendered here as “Cloud Irons”), horizontally cantilevered skyscrapers, inspires a digression into the Soviet fixation with colonising the sky and eventually space. Lissitzky sought to create a new plane on which human life could be conducted, elevated above the feudal skyline of Moscow and more expansive and ambitious than the narrow heights reached by cloud-piercing American towers. The Wolkenbügel were no more than castles in the air but the Soviets did colonize the skies in other ways—in pioneering trans-polar and high-altitude flights, celebrated in charts and propaganda posters (“What did you do during those great Soviet flights in 1926?”); in triumphant passes of Soviet aircraft over Moscow, commemorated in postcards. Unable to physically construct a higher plane of living, Lissitzky located it instead in Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist paintings and designs. Their floating geometric forms and stark minimalism gesture at fourth dimension beyond ordinary perception and evoke feelings of weightlessness and higher consciousness that simulate flight. The avant-garde saw flight and space as metaphors for the Soviet experiment and as means of inculcating in the Russian people a revolutionary consciousness. Constructivist artist Rodchenko designed cufflinks with aviation motifs, and Lissitzky crafted a Supermatist children’s book, depicting extra-terrestrial squares that come from space to rebuild the Earth (and acclimatize children to the artistic vernacular of the revolutionary age). The Soviets also harnessed flight to more literally spread propaganda. A flying agitprop machine and largest plane of its age, the ‘Maxim Gorky’ carried a rotary press capable of printing 10,000 copies an hour, a laboratory to develop photos taken from the air, and a cinema screen for 10,000 viewers. It flew all over the Soviet Union raining pamphlets onto the masses below before—metaphor warning —crashing during a demonstration flight over Moscow in 1935.

Other Soviet schemes for public enlightenment were more earth-bound, although no less doomed. Ivan Leonidov’s Lenin Institute was to collect all human in one monumental, futuristic sphere, complete with 15 million books and tracks of conveyor belts to fetch them, a planetarium, auditoria with moving walls, and complex circuitry of telephones and radios to allow the academic staff to collaborate and broadcast their work to the entire Soviet Union and the world. Like other Soviet intellectuals, Leonidov was fascinated by the utopian writings of 16th century Italian friar Tommaso Campanella and his vision of an egalitarian City of the Sun, where architecture was a didactic tool and seven concentric rings of walls organized society and set it in orbit around a central temple of knowledge.

Ultimately the Lenin Institute was as hypothetical as Campanella’s City of the Sun but its ideals–of edification through architecture, of the primacy of knowledge—seeped into Soviet society. Mobile libraries travelled the Russian rail network, bringing light to all eleven time zones of the Soviet empire, including tens of thousands of copies of Campanella’s work. Plans for communal housing, including Nikolai Ladovsky’s, sought to dismantle the nuclear family and liberate women from the drudgery of housework through architecture, giving them time for self-improvement. Ladovksy’s Communal House took the form of a crooked, ascending spiral, a form that critic Nikolai Punin, defending plans for the most famous Bolshevik spectral building, Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, described as “the line of movement of a liberated mankind… rear[ing] from the ground, escap[ing] the world, and ris[ing like] a beacon dispelling all that is motivated by the bestial and mundane.” Again, the Communal House was never constructed, but its sketches provide entrance into Imagine Moscow’s exploration of Soviet womanhood, in albums depicting their participation in the “construction of the USSR,” posters heralding the establishment of communal kitchens and nurseries. Again, propaganda outpaced reality for most Soviet women, who could never escape the burdens of housekeeping and childcare, no matter how the government celebrated them in posters and promised “factory kitchens.” And the collective housing that did emerge—created more as an emergency response to a housing crisis than out of ideological conviction—were crowded apartments hastily subdivided into rooms for as many as seven families.

Architecture was to shape and liberate not only the mind of the New Soviet Man (Woman), but also his body, as Nikolai Sokolov’s Health Factory Black Sea resort for Muscovites illustrates. Consisting of individual capsules for rest, joined to communal spaces for eating and “socialist leisure,” the Health Factory manifested the ideal balance between the individual and the collective in a socialist society. The Soviets viewed the body as machine, requiring exercise, recuperation, and repair, whether in “health factories,” or on actual factory floors. Aerobics routines were incorporated into workdays and the “Ready for Labour and Defence of the USSR” programme encouraged citizens to earn badges by passing 21 fitness tests.

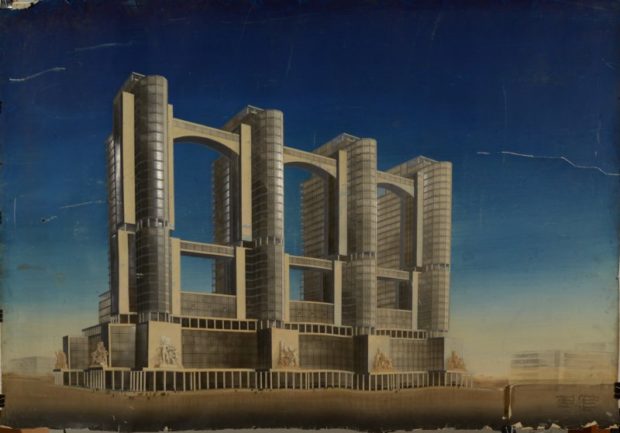

The final two hypothetical buildings in the exhibit–the Commissariat of Heavy Industry and the long-delayed Palace of the Soviets–were anchors of a Stalinist master plan for Moscow. Bombastic and heavy ornamented, they were not only aesthetically removed from the avant-garde geometry of earlier Bolshevik paper architecture, they emerge from a different ethos. No longer molds or factories for a new socialist world and a man to inhabit it, buildings in the Soviet Union were now intended to monumentalize and celebrate what the Soviets had achieved–the first phase of communism that Stalin triumphantly announced had been realised by 1936. Konstantin Melnikov’s entry into the design competition for the Commissariat saluted, in figurative sculptures on twinned 40-storey buildings, the successes of Stalin’s first and second five- year plans. But any manifestation of the Commissariat would have been dwarfed by perhaps the most infamous boondoggle ever: the grandiose Palace of the Soviets, intended to be the tallest building in the world. Following a competition Stalin personally selected a design by Boris Iofan, in the wedding-cake, hyperbolically classical style that came to characterize Stalinist architecture, and topped with a nearly 100m statue of Lenin, pointing. Construction began in 1937 but was interrupted by the German invasion in 1941, when parts of the steel frame were stripped for use in Moscow’s defense fortifications, and never resumed. In 1958 the foundations were converted into the world’s largest open-air swimming pool. Film footage shows Muscovites enjoying some good old-fashioned socialist leisure in its waters. A model of the 4-metre index finger with which the colossal Lenin was intended to point stands in a dark corner here. It’s both a ghost and a gag.

The only completed structure of those featured is the mausoleum in which the ultimately mortal and life-sized Lenin would be interred: a hulking marble and granite pyramid, designed by Alexey Shchusev to echo ancient tombs. But even this structure is haunted by the unbuilt. Entries into the competition for its design, from engineers, students, and peasants, are projected onto the walls. With electrical bolts, soaring towers, and strange geometry, they’re evidence that Soviet imagination and idealism didn’t wither under the political and architectural totalitarianism of creeping Stalinism. Imagine Moscow could be defeatist, its phantom structures easily be dismissed as boondoggles or reduced to metaphor–for the icarian arrogance of revolutionary schemes, for the grim trajectory of the Soviet experiment. But with imagination and some generosity, they’re monuments to a lost idealism, to the human capacity to dream outlandishly. As our own city undertakes a piecemeal, private transformation—no Underground line extended without developer cash, no social housing spared social cleansing regeneration, no vision of its future complete without a hundred Prets—the audacity of these Soviet hypotheticals is exhilarating.

Imagine Moscow continues at the Design Museum until June 4. Tickets are £10 (£7.50 concessions).