You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

It is an almost universally accepted cliché that a poet´s career is a solitary one; Dylan Thomas would talk about a “sullen art”, even if he was an energetic communicator of his own verse in public readings. It is precisely when reading or saying verse before an audience that the poet has one of those precious occasions to question the craft, a craft which is normally attached to the written page and embedded in the literary tradition.

Actually poetry antecedes literature, the letter and, obviously, the printed book. Sometimes we forget this when we’ve devoted more time to the page. For thousands of years poetry was closer to dance and music than it is today. The instruments and functions of the poet underwent a progressive reduction until poetry became, practically speaking, a matter of words fixed to a sheet of paper or a computer screen.

That could account for the fact that improvisation is not one of the most frequently used tools of the craft. As a matter of fact, outside of jazz and happenings or a few theatrical exercises, improvisation does not have such a good reputation in an art and literary world which is still overseen by academic and utilitarian perceptions of creativity. Slowly, slowly, who knows throughout how many centuries and cultural operations, improvisation has become almost a synonym of sloppiness, lack of preparation or concept, in other words a deficiency in craft.

We look around at the other sister arts and wonder how specialization and pre-meditation become naturally necessary for the creative process. How much improvising do we need at the point zero of creativity? While avoiding a general overview of that which, again, Dylan Thomas called “the history of the death of the ear”, I would to try to understand how the theater, music and dance can become a common area for a renewal of the perception of poetry and, eventually, the writing of poetry.

Perhaps it all begins when you feel a certain discomfort in the notion of poetry as a literary genre; how is it that an open source of knowledge, able to inform our perception and production of sounds, colors, feelings, movements, not to mention ideas, can be enclosed in only one type of mental structure or discourse? You can say, of course, that such is precisely the magic, flexible condition of the poem: to contain worlds within a few letters. And that would be right, yet a poem knows that there are other worlds before and after its completion. If poetry is not only a literary genre, then what is it or what more can it be before and beyond the page?

It is crucial to notice that other artists also feel the same discomfort within their respective limits of specific arts or genres. Watching a film by Andrei Tarkovsky, say Mirror, or reading Artaud as he describes the actor as “an athlete of the heart”, or listening to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, or looking at a painting by Rothko, one feels that there is more to it than the use of a single artistic structure or craft. There is such a flow of meanings, such an interaction of those methods of “doing” that we call techniques that one single specific art form would not be enough to encompass works of the kind. Furthermore, we can observe in them the common trait of improvisation.

I started to study improvisation in the theatre; even if in Cuba a strong tradition exists, especially in the country side, of stanzas improvised to the accompaniment of folk music, a “literary” poet very seldom is expected to do so: he or she is supposed to write and not to sing aloud whatever comes to the mind in rhymed form.

I was lucky enough to find a man whose theatrical method was based on improvisation, not exactly as a technique but as a source of self-knowledge as well as of comprehension of the Other. His was a mirroring method based on a You and I line of attention. In his view, spontaneity could be learned and practiced deliberately sometimes leaving to the artistic result the possibility of being just that, a result and not a goal in itself, however valuable.

The thought that all what we do must serve a purpose and bear some gain has contributed more than any other artificial or natural disaster to keep the human species in a state of bondage and art is one of the few windows left to a world of non profit. Art must be profitable in itself or not be profitable at all. That is probably why we look for an alternative to the bondage of profit and start to think of art as a process and not as a factory of artistic results. In this moment, the practice of improvisation becomes crucial.

This man came from a theatre family and had been working for years on behalf of sincere and playful acting. I saw him once as the Fool in The Twelfth Night, playing between stage and audience, making fun of the characters as well as of his fellow actors attracting the audience towards the embarrassing wonder of look- at- yourself- looking- at- the- theatre. He emphasized the meaning of theatre as something related to the action of looking. His name was Vicente Revuelta.

He encouraged the use of live music and singing and eventually with a couple of professional actors and a bunch of amateurs, we managed to assemble a Brecht Cabaret: one small piece about a beggar, an emperor and a dead dog, one poem, “Baal”, an acting exercise based on Auden´s poem “Musée des Beaux Arts”, two songs from Mother Courage and some drumming and dancing. And one collective creation: an acting exercise based on Auden’s poem “Musée des Beaux Arts.

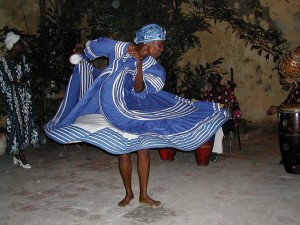

Drumming and dancing was sort of an informal action also happening before and after the show. At a certain point of the night, while the performers were singing one of the songs, they shared bread and tea with the other participants—that is, the presumed audience or public which was all over the place sitting, walking or standing inside and outside of the open barn-like garage.

We were learning the interaction between improvisation and result, between process and structure. The night show arrived after a day of improvising and was improvised in itself from a structure of text, music and action.

We can see improvising as a departure from clichés as well as an investigation of clichés, not only in the intellectual arena but with physical movements and the expression of emotions.

One cliché about improvising is that it doesn’t need a structure, that it is even the opposite of structure. Actually structure and improvisation are close relatives, like brother and sister, like delicacy is related to strength, as in smell or sound.

You can improvise about a commonsense idea of what a structure is or should be: something firm, fixed, symmetrical; as much as you can write the structure of a play using a series of clichés about improvisation: you don’t know what to do now or next, you go crazy, act like an animal, crawl, howl, uttering unintelligible sounds…

Improvisation can surely make us look ridiculous, on the stage as much as in everyday life. It can make us be ridiculous. Since the idea of what is or is not ridiculous is also based on stereotypes, it can be improvised upon.

Musical premises exist to be defied through improvisation. Can “pure” and “spontaneous” coexist in the interpretation of, say, flamenco? How original is swing? How somniferous should lullabies be? Anything, from blues to Bach, is indeed improvisable and thus translatable.

Translation is also a form of improvisation; no one word means the same thing at all times and places. Only at a specific time and place does the word have a specific meaning. In Heraclitean fashion, improvisations are often described as flux away from crystallization. Then, how can the structure flow within improvisation? It is a topic that has triggered such books as Finnegan’s Wake, with a structure as flexible as sound can be. The sound of the words is just as important as their meanings—that is, we can understand sound as meaning.

I feel moved and encouraged by the fact that such people as Aristophanes or Sophocles were and are still considered poets; at the same time, it puzzles me how in Shakespeare’s time a poet was apparently a different thing from what Shakespeare himself was, not to mention Omar al Khayam, an astronomer and mathematician who is better known as a man wrote a number of songs for his friends. And how “off the page” are Carroll’s adventures improvised while drifting in a boat with two kids?

The ways of poetry, in fact, wander a lot outside the literary reservation, though there is no Poetry Channel to inform us about such possibilities.

Spontaneously methodical, as E. E. Cummings would put it, improvisation opens a view towards the building of a structure, whether in book, song, or dance choreography, which does not rely on preconceptions; structure thus becomes part of the erotic phase of conceiving work as a tool of happiness or, if you prefer, as fun. All this, of course, is a cliché about improvisation, one that the page very well permits.

The other side of the Wall that protects poetry against improvisation may also be covered with beautiful clichés because we are producers of preconceptions and concepts; writing could be conceived, from this perspective, as a mental machine within that other machine that the writer is.

Then, in dance or painting we observe the same production of common places. Now they are not only intellectual but also executed through movement, rhythm, colour. It is precisely because everything, around us as well as inside us, is so full of clichés that improvisation exists at all.

The Japanese renga is a combination of improvisation and stereotypes about season, nature, time of the day, weather and other common perceptions of life. A group of poets gather to compose, one haiku after another, a sort of cantata inspired in the moment by using those stereotypes as basic, imaginative tools.

The structure of renga can be applied to another flexible and marginal space such as the cabaret, and the initial process of translation from, say, nature into words can be re-translated then into music and dance spinning around a subject. Once I participated in such an experience focused on the topic of translation. An actor or dancer improvised a haiku departing from a clichéd posture of how she or he imagined a poet to be. Then, the music tried to grasp the essence of the poem while a second dancer or actor improvised. A second poem would then materialize from the image of the actor-dancer.

Whereas the experience of traditional renga could be for a contemporary poet no less uncommon than playing with a jazz band or acting in a play by Artaud, it is also a fact that the participation of the poem itself in music, theater or even dance is not so rare. Poems travel all the time and they are surely more flexible than what very often their authors can be.

Sometimes an attempt can be more impressive than certain predictable results.

About Omar Perez

Omar Pérez from Havana, is a prize- winning poet, essayist, and Zen Buddhist monk. He received Cuba’s Nicolás Guillén Prize for Poetry for Crítica de la Razón Pu- ta (2009), and its National Critics’ Prize for his essay collection La perseverancia de un hombre oscuro (2000).