You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

What makes us start writing a diary? The dawning of another year? Or perhaps the beginning of a whole new life? I am sitting in the sunlit Paulson Reading Room at the University of Oregon in Eugene, reading the diaries of women who have been dead for over a century; women who embarked on such a great adventure that they decided it needed to be committed to paper in the pages of a daily journal. As part of my research for a novel which follows the journey of a Victorian woman from Liverpool to Oregon, I am digging into the archives to read the true stories of those who travelled the emigrant trails in the mid-nineteenth century. [private]

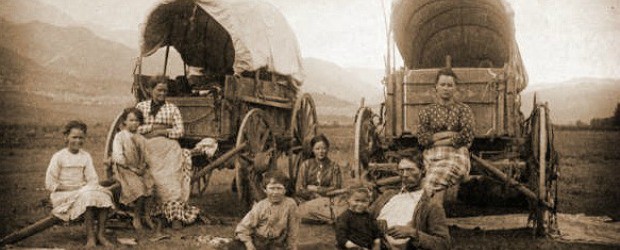

At each end of the Reading Room, carved in thick cedar wood, hang triptychs depicting the history of this western state. One of the images shows a wagon train negotiating the Barlow Trail at the foot of Mount Hood. It is a picturesque scene, with the tall trees, mountains and rivers which contribute to Oregon’s astonishing natural beauty. It reveals little of the nightmare of hauling wagons through impenetrable forest, across freezing rivers and down treacherous mountainsides, or the personal tragedies caused by illness, injury and death. In the 1850’s this land was yet to be ‘tamed’ by white settlers, but increasing numbers were tempted to brave the gruelling journey to the Oregon Territory as part of the ‘Manifest Destiny’ to expand the boundaries of the American nation. With the promise of cheap, or even free, land, many saw it as an opportunity not to be missed. For most, the trail began at St. Joseph, Missouri and ended two thousand miles later in the fertile Willamette Valley, Oregon. The popular image of families packed into horse-drawn wagons to cross the windswept prairies is misleading; wagons were small, no wider than a double bed, and only the sick, elderly or very young were allowed to take up precious cargo space. Everyone else walked, and the wagons were usually pulled by less romantic, but far more resilient, oxen. How do we know this? Largely by reading the letters and diaries of the emigrants themselves.

Should we read someone else’s diary? Normally, perhaps not; it’s a repository of secret thoughts, fears and dreams that are never intended to be shared unless they belong to an individual whose life is of public interest, say a politician or a film star. But what about those everyday people whose scribbles in a journal are simply meant as a private means of self-expression, a place to rant about an unfeeling lover, difficult relatives or trouble at work? Sometimes, opening the diaries of these wagon train women, I feel something of an intruder. When I read the entry for 19 May 1853 written by nineteen year old Agnes Stewart, it is hard not to be moved by the anguish she tries so hard to conceal:

“Oh, I feel so lonesome today! Sometimes I can govern myself, but not always, but I hold in pretty well considering all things.”

Agnes confides her private suffering to a journal, not wanting to be seen by her fellow travellers as a weak and complaining girl. Fixing a lantern to the ridgepole of her tent, she sits hunched over her diary at night, desperately missing family, friends and a familiar life left behind. As the entries continue, my impression of the character of this young woman becomes clearer. She is sensitive to the plight of the Native Americans, questioning their treatment by the government; and she is clearly distressed by the discovery of a woman’s corpse, dug up by wolves, blue ribbons still intact in her hair. On days when the wagon train rests, Agnes tells us she is doing laundry, or stewing apples, though she longs to swim in the creek or play leapfrog with the boys. Although it seems that this diary was written only as a private outlet for thoughts and emotions on the emigrant trail, the document was preserved long after the journey had ended, and, indeed, after its author had died. Can we assume that Agnes kept it to remember that turning point in her life? Did she intend it as a record of family history to pass on to her children and grandchildren? As the teenage Anne Frank recorded in her own diary in 1944, “I want to go on living even after death.”

Of course, there were some, like Elizabeth Wood, who started their diaries with the intention of getting published. By the mid-nineteenth century, pioneer journals had become commonplace, although those published had generally been by men. Elizabeth was unusual in that she was female and single, following in the footsteps of successful women travel writers of the time, such as Isabella Bird Bishop with her book A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains.

The original diaries written by the emigrant women were small notebooks that would take up little space. Paper and ink was in short supply on a journey across the continent that might take four months or more. Space in the wagons was reserved for food, and essentials such as bedding and cooking utensils. A journal that could slip into a pocket with a pencil would become a treasured possession. Few of these documents have survived, but many were transcribed before the contents were lost, either by the women themselves, or often by daughters, nieces or granddaughters. Here in the archives, I am reading a diary originally handwritten in 1852, and typed up some sixty years later. The ink is faded, the typing uneven and smudged, but this only serves to remind me that this was probably intended as a personal, family document. It is only with the passage of time that the accounts of ordinary people assume the importance of historical commentary.

Some of the diaries highlight the writer’s awareness that she is entering a new chapter in her life, with the potential for success or failure, happiness or grief. Writing on 4 January 1851, Jean Rio Baker starts her New Year boarding a ship from Liverpool to New Orleans, on route to Salt Lake City.

“I this day take took leave of every acquaintance I could collect together, in all human probability never to see them again on Earth. I am now (with my children) about to leave for ever my native land.”

Is she sad at these partings? It would seem so, but there is also a frisson of excitement. Later, when describing awful storms in the Atlantic, Jean writes triumphantly that she is one of the few passengers unaffected by seasickness. Her diary entries are regular, part of her daily routine. Maybe this is an antidote to boredom, or perhaps a method of alleviating fears for her children and herself. Even when her young son, Josiah, dies, she manages to record the event in her diary, noting the exact longitude and latitude where his body, sewn into a white sack, is consigned to the deep. Her grief is palpable, yet Josiah is not mentioned again after this date, his mother’s diary now preoccupied with the illness of another child. Does that daily ritual of taking up her journal help Jean to keep going, to press on with a journey despite the costs?

Jean Rio Baker’s account of life on board a ship full of Mormons heading to Salt Lake City contains fascinating insights into the life of this community. When the weather is calm, and the family are well, she has time to write of the “shameful” behaviour of Elder Booth and Sister Thorn who are thrown out of the church. We are similarly intrigued by her brief mention of three Mormon women who are cut off for “levity of behaviour (with some officers of the ship)”. There are descriptions of meals, musical evenings and stunning sunsets. On arrival in New Orleans, she uses her diary to debate the issue of slavery, and to dissect the social customs of Louisiana society. As her journey progresses up the Mississippi River to St Louis, and beyond on the Mormon Trail to Utah, Jean writes almost every day, despite broken wagon wheels, perilous ravines and unpredictable Indians. She records attending births (including that of her first grandchild) and deaths, nursing those who are injured or ill. When she finally reaches Salt Lake City, she describes her joy and gratitude to God for arriving safely. Yet we also detect a wistfulness that the adventure is over and her diary with it: “and now I suppose I have finished my ramblings for my whole life.”

Whereas Jean completes her regular diary entries despite the rigours of her daily life, other women struggle to find the time between childcare, cooking and laundry. Perhaps Jean, being a widow, has more control over what little free time she does have. Eugenia Zieber writes almost always on Sundays, when the wagon train halts to observe the Sabbath. However, there are several false starts in her journal, where all she succeeds in writing is the date. Her frustration, as well as resentment of those who have lighter responsibilities is evident:

“There is scarcely time, upon such a journey, for those who have aught (sic) that is essentially necessary to do, to keep a diary. It must be done by snatches or at any moment or not at all.”

Eugenia does not explain her motivation for her desire to write. Perhaps she wanted to capture the inhospitable mountains that threatened snow even in July, or wolves that howled on the fringes of camp at night, or the immigrant names carved on Independence Rock. All we can be confident of is that the ritual of setting down her personal thoughts and observations in a diary, on a daily, or at least regular, basis, is important to her.

The more I investigate the journals of these women who undertook the challenging immigrant trails, whether to Oregon, California or Utah, the more I recognise that they were just like us. They record the daily trials of marriage, children and neighbours, domestic chores and inclement weather. Although their diaries document a singular event that shapes their lives, they also reflect the history of an expanding nation, and the role of women within it. These are strong women, whose individual voices speak to us generations later. Glimpses of burgeoning feminism are seen in references to wearing practical ‘bloomers’ instead of trailing skirts. There are joyful descriptions of novelties such as prairie dogs, cacti and buffalo (although the latter may bother the cattle driven ahead of the wagons).

There is (perhaps unwitting) humour, such as in Mariett Foster Cummings’ diary entry in April 1852 on her way to California:

“This I expect is the beginning of trouble. I stayed at a public house and ate fried pudding.”

There is great sadness, as scribbled by another woman:

“I am sick. Sometimes I think I shall not live long. It is hard to die so young and William, my William, who will console him?”

She’s not being maudlin, just realistic; hundreds of women died on the emigrant trails, both in childbirth and of illnesses such as typhoid, malaria or dysentery. Not to mention those who drowned in raging rivers, fell under wagon wheels or were killed by hostile Indians. Acutely aware of the fragility of life, the women cling to their diaries. If they should die along the trail, and be buried in a shallow grave without a tombstone, at the mercy of wolves and buzzards, there will be nothing to show for their lives. A diary at least would leave something behind. [/private]

About Claire Thurlow

Claire Thurlow is a writer and researcher. She first stumbled across the Oregon, California and Mormon Trails during the ten years she lived in the USA, and recently retraced some of these steps. Her discovery of the diaries of the wagon train women inspired the novel she is now working on. She has recently contributed to an anthology, 'Reflections on the South Downs', and is a Postgraduate Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Sussex, reviews books for the Historical Novels Society and teaches in Surrey.