You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

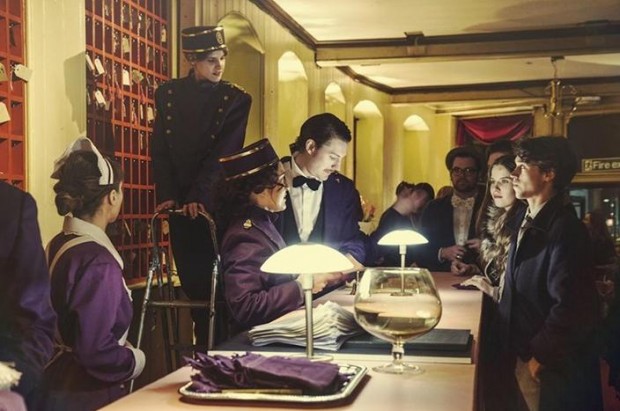

Few productions I’ve seen have made quite so many demands upon its audience as Secret Cinema’s interactive rendition of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Guests are strongly encouraged – a melange of request and command no less elegant than that evinced by master concierge Gustave H. in the film itself – to don formal 1930s-style attire, to learn the waltz, to bring one of four “gift” objects, to memorize a poem, to print out an official “Guest Card” complete with photo identification and to familiarize themselves with a lengthy cultural history of the Republic of Zubrowska: a Central European country of indeterminate border where dispossessed dowagers and dissolute émigrés alike take tea and play cards at grands hotels.

Such demands proved, by turn, exhilarating and infuriating: at once successful in inviting a far great degree of involvement from audience members and maddening at the degree of promise unfulfilled. When I was stopped at the Zubrowska’s “border” by a black-clad goon with a suspicious scar, chastised for not having my visa in order, and finally helped along in exchange for my Guest Card and the promise of a future favour to be extracted, I was convinced that the effort of finding a print shop in Central London was worth it: that my eagerness to be subsumed in the world of the story would be met, in turn, with some form of a place in it.

Not so. The goons never collected on their favour, leaving me to find my own way to their leader, involving myself in the story of a deceased noblewoman and the contested fortune (including a priceless painting) she’d left behind: a narrative thread that seemed to involve a few hiccups, such as characters changing names halfway through (one character I was sent to find was referred to by the Grand Budapest’s denizens as alternately “Gregory” and “Dmitri” – the latter, I came to realize, his name in the film only – making tracking him down more onerous than it should have been). So too the confusing nature of one of the show’s props, a newspaper set in 1932 and available throughout the hotel lobby. While the front page cover story, warning of the onset of war in Zubrowska, did much to set the scene, other articles were outright anachronistic (one referenced a Leonard Cohen concert), destroying the sense of place Secret Cinema seems to be working so hard to provide.

While most of the scenes of interaction I came across were engaging and thoroughly convincing – the actors, particularly the one playing the shoe-shine boy, were all charismatic and more than comfortable with the challenges of interactive theatre – such minor hiccups detracted from the overall unity of the hotel’s atmosphere: making me feel, at times, that all my advance preparation had been in vain. (Of the four choices for a “gift,” I only saw a use for one during my ninety minutes in the hotel.)

At other times, however, the amount of effort audience members had been called upon to put in worked in our favour. Decked out in period costumes, many of us were indistinguishable from the actors, and I had more than one exchange with a “character” during which neither of us was sure if the other was a performer, allowing us to expand the borders of Wes Anderson’s imagined Zubrowska a little further.

Zubrowska and the Grand Budapest are splendidly realized on Secret Cinema’s Farringdon premises. From the grand hotel lobby to the thermal baths to the somber town house of the deceased dowager, each set piece is meticulous and thorough. The action, too, is well-placed, allowing for a natural delineation between audience members who wanted to focus the vintage cocktails and those – like me – who were racing around in search of the action, tracking down characters in search of that mysterious painting. But at times, the world of the story seemed more evoked than fleshed out; an atmospheric setting that fell short of telling a story in itself – a disconnect that became all the more apparent after watching the film, which melds form and content rather more skillfully.

It stands to reason that atmosphere, rather than narrative, is Secret Cinema’s stock in trade. But given the emphasis the company puts on active audience participation, it should be far less easy to accidentally peek behind the curtain of the fantasy.

Secret Cinema Presents: Grand Budapest Hotel continues until March 30th. See the Secret Cinema website for more information. Read our review of the film here.

About Tara Isabella Burton

Tara Isabella Burton's work has appeared or is forthcoming in Arc, The Dr TJ Eckleburg Review, Guernica, and more. In 2012 she received the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize for travel writing. She is represented by the Philip G. Spitzer Literary Agency of New York; her first novel is currently on submission.