You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In the mornings the fishing boats collect. In the grey-blue mist of the nearly-light they arrive at the harbour mouth, their decks heaped (or not) with last night’s catch. Here the fishermen’s voices practice themselves again, calling out a ‘hey-ho’ or a ‘bring ‘er in’ in the dry-throated singsong of men who live and breathe with the sea.

As the mist disperses the boats become distinguishable from each other. New and old, poor and less so. There is the difference between a high-heaped good catch and a meagre one, and some of this is down to luck. There are the telltale marks written upon the boats by the fishermen: patches repainted, storms smoothed over, boards fixed. Inside the boats there are magazine pages and old photos taped to walls. There are tin plates, paintbrushes and woolen clothes stowed into cupboards where a storm won’t pull them away.

[private]And as the grey-blue light gathers a green to it, lets in a yellow just appearing over the flat-out waters, the men are throwing ropes to the shouts and jumps of harbour workers who are peeling from their houses, pulling on their overalls, swigging dregs of coffee and stamping down their boots. Gulls lift with a caw-caw, and smoke whispers up from the chimneys of houses as the hot smell of toast is forgotten with the incoming stench and promise of the sea.

And upon the heavy stones of the harbour wall the men of the sea exchange fish and a few words with the villagers. News is passed on, necessary repairs are made. And before long the fishermen’s eyes begin to wander. They will notice the hardness and stillness of the stone, and listen to the lapping and teasing of the water at the wall, and soon they will return to their boats, pausing again at the harbour mouth before dipping and nodding their way on.

This is how it is and how it has always been in places where landpeople live with the constant crash of wind and waves, the comings and goings of the seafolk and the rhythm of the tides. In these places the villagers look out not with longing but foreboding, and the tides (and so perhaps the fishermen) are a mystery few have the time or inclination to understand. Interested only in what the ocean brings and takes with it, they are dependent upon it, and fearful of how it shakes them. So there is always an air of restraint, a guardedness to the exchanges between the fishermen and the villagers along the hard stonewalls where land and sea collide.

But this was the morning that—among the ropes and the dry throats and the caw-caws—a fisherman stepped down from his boat, bow-legged, swaying still with the motion of the waves, and drifted past the harbourmen. Floated silently up the street where steam rose from cooking pots and down an alley where morning hadn’t woken yet. Finding his feet were carrying him he walked on, beyond the village. Moving no further inland and always keeping half an eye on the ocean, he began to trace a coastline.

Navigating not according to points in the sky but the winding of a well-trodden path, he walked high up and looked down at how waves gutted at cliffs below. And as the sun rose he came to an estuary where the sea slipped in among hills wide and quiet and free. Where wordless sounds carried out across empty sands pockmarked with the imprints of birds and regurgitated tracks of sandworms burying down. He stood there—a man cracked dry and salt-encrusted—and felt a change in him.

He sat down and looked out and might have stayed there, not noticing that he was leaning against a gate, and that the gate opened onto a path, were it not for a young woman—broad-shouldered and barefoot—walking along it and towards him.

She opened the gate with a jerk and he fell at her feet. She lifted a toe to give him a prod, and as his form rocked slightly under the pressure she was reminded of the waves. She looked down at his cracked face and felt a moisture rise up. He, a little dazed, lifted his head and smelt earth on her bare foot. They found each other’s eyes and felt the wind about them.

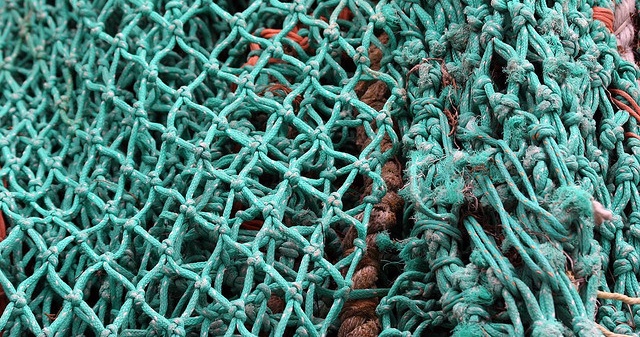

For seven days and nights he unsuspends himself from the sea. Under open skies they float over the sands of the inter-tidal zone. She feels the throwing and hauling-in of his nets. The tossing and pulling back, tossing and pulling back, and the looseness of the sea. In the shelter of sand dunes she pulls up grasses to show him their roots, and he peers at the white tendrils, finding them both peculiar and strange. When he speaks he tells her about the ocean, which is all he knows. About a life lived in silent conversation with the sea. How food is caught and not cultivated, how the changing seasons tell the movements and migrations of fish and the shifting moods of ocean currents. How a fisherman must tend to his net, which is also his lifeline. He touches her with his rope-worn, mollusced hands as she, reeling, smells how deeply the fish and salt have penetrated his skin and feels a little afraid. At night she wakes and looks up at the stars, which appear different now, and not so far away. She feels how he holds onto her feet in his sleep, lying curled up like a baby or the tail of a seahorse. They hold onto and swim around each other, and he who had never known a longing, who had lived life according to the only needs he knew—food. water. fish. paraffin,—is caught off-balance. They live like this for seven days.

And on the eighth day the moon pulls at the sea and a springtide rises over seaweed stretch-lines. Wader birds gather in anticipation as the water creeps up and laps at the toes of the couple lying in a small cleft or a hand-hold in the sand. The fisherman wakes up and looks down and sees the tide has come as far as it will go. And as the moon loosens her grip the sea draws back taking a fisherman with it, bow-legged and swaying slightly. He follows a line along the shore, ankle-deep in water until he comes to a harbour, where there are shouts and ‘hey-ho’s’ and boats tipping back out, and then on.

It is so rare for a fisherman to leave the wave-tossed life of the sea that when on occasion it happens it seems to draw stories to it, become wrapped up in folklore and pulled out from time to time in the corners of public houses where harbourmen sit and listen to the sounds of their own voices gather in. On cold winter’s nights, loosened and encouraged by warmth and drink, they tell uneasily of the land-woman who lost her heart to the ocean. No-one saw her where she woke in a hand-hold and found herself alone; no-one heard if she cried out. So no-one can be certain what happened as she stood up and watched wader birds pick at what the tide had tipped into rock pools and left strewn out along the beach. But now and then reports reach them of a small house perched upon a cliff not so far away, with a garden and a small gate to it. And so the harbourmen have composed a picture in their minds of what came next, and this picture alters sometimes according to their moods, since it is alarming to look at, and sometimes they can’t. A garden growing on a cliff-edge. Dried-up soils opening only to the harshest of plants thrown back, growing strangely up but away from the sea so that they appear half-fallen, covered in a fine salt like clinging dust, their roots forcing resolutely down. In the garden they see a woman with cheeks burnt red from the sting of ocean winds, a spade in one hand and a wildness about her. They watch as she digs with a restlessness, pulls at the earth with a longing it refuses to hold. They falter here, the harbourmen in the corner, and fall into a silence broken only as someone tells quietly of a fisherman with feet as dry as the sand, who can be seen each time the springtide lifts, wandering and adrift at the edge of the sea.

The men look down and see that their glasses have emptied and notice that the lights are low, the chairs upturned already on every table but their own. They look around, bewildered, and reach awkwardly for their coats. The woman at the bar calls over to hurry them on and they like children look gratefully up, reassured, feeling their singsong voices return to them as they sweet-talk and tease her across the room, knowing she’ll smile, seeing she does. They pull open the doors and a shock of cold air sweeps in. She turns and picks up a broom as outside they lean over each other down the cobbled-up street, swaying slightly, pushing along the sea wall and out into the night.[/private]

About Helen Jukes

Helen Jukes lives in a house by the sea on the South coast of England and works part-time for a small charity based in London. She is interested in writing that challenges us to listen and look at the world around us in new ways. She believes Literature can take us places; can lead us to rediscover our own environments as well as ourselves. She has previously written non-fiction for Resurgence magazine, Caught by the River, and BBC Wildlife.